Blue Smoke: The Past, Present and Future of Our Cars

New Zealand has one of the oldest, least efficient and largest vehicle fleets per capita in the developed world. How did we get here and where are we going?

By George Driver

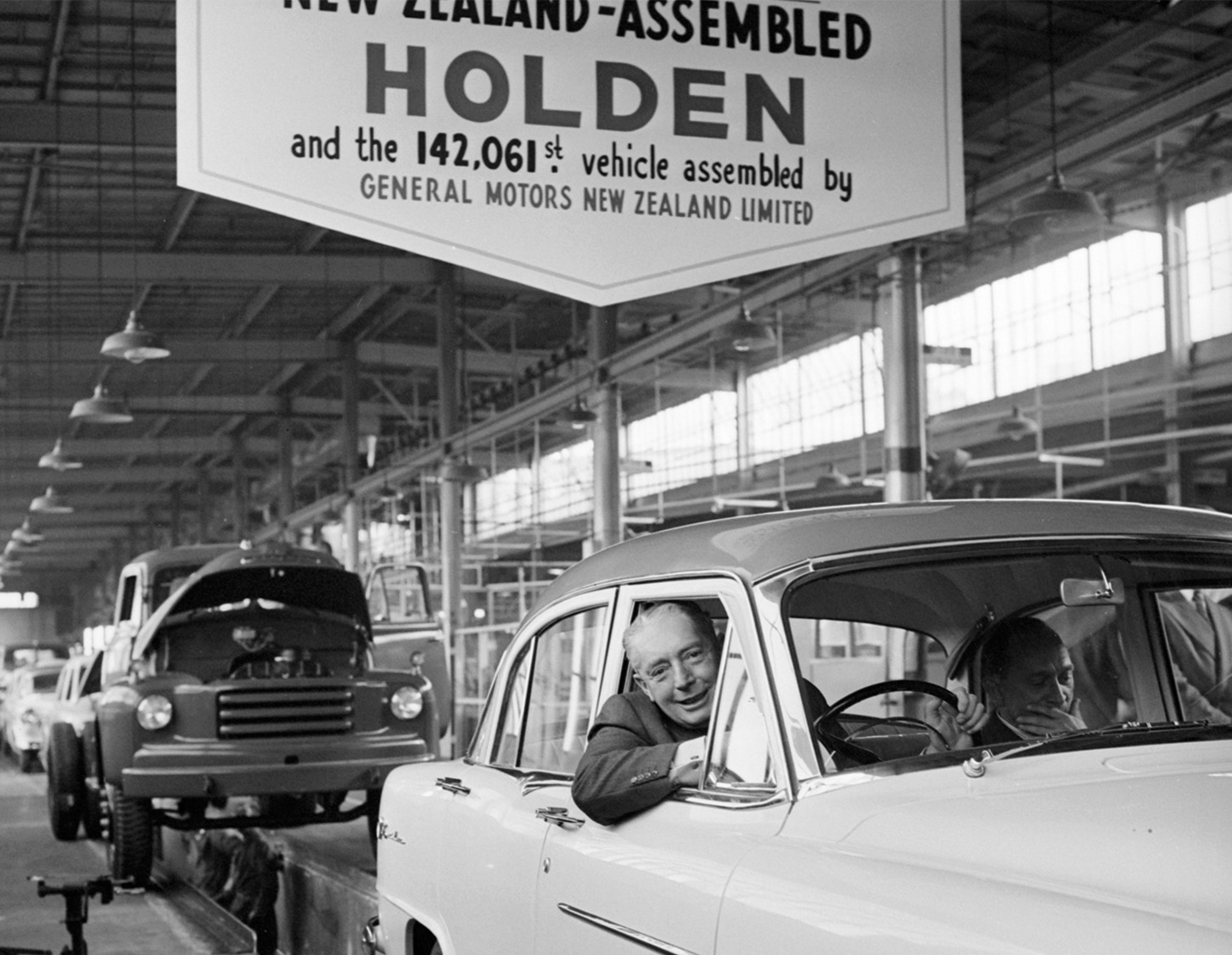

Photo: Basil Williams, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections

It just won’t die, but I can’t bring myself to kill it off. I bought my first car — a 1996 Nissan Sentra — for $1500 from Dunstan Motors in Clyde on 18 December, 2013. It had already travelled 243,000 kilometres. The paint was peeling off the bonnet, even then. The patterned grip on the steering wheel had been worn smooth from 17 years of use. The rear electric windows didn’t function at all. But for the first time I could go wherever I wanted, whenever I wanted.

I bought it to drive all the way to my first real job, working as a journalist for a little paper in Warkworth, north of Auckland. My partner and I left on Boxing Day and over the following two weeks the Sentra became our home. In the years since, we’ve driven the length of the country many times more, putting another 115,000km on the clock.

It’s been reliable, if not problem-free. There have been many AA callouts, most recently in March last year. My partner was seven months pregnant and driving — I had my hand bandaged up in a sling after some minor surgery — when the engine stopped, the electronics went and we silently drifted down Dunedin’s Maitland St towards Kensington Oval. We pushed it across a fortuitously deserted Princess St and into a free park. A new fuel pump and $400 later and we were back on the road.

As our due date approached, Marielle began suggesting we get a more reliable vehicle, something with more than a single-star safety rating and rear windows that actually work. We got a used Subaru Impreza, not long off the importer’s ship from Japan. Although it’s already 10 years old, it feels like a new car.

I tried to insist that we needed two cars, but that circumstance has never occurred. So for the past year I’ve been grappling with this dilemma: What should I do with a vehicle so old it’s almost but not quite worthless? Is it better for the environment to send it to the scrapheap, or sell it on for another owner to eke out a few more kilometres and prevent wrecking a car that, despite its faults, is still functional?

It’s a conundrum that generations of Kiwis have faced. New Zealand has one of the oldest, least efficient and largest vehicle fleets per capita in the developed world. As of 2020, the latest figures available, there were a record 4.4 million vehicles in the country, 90 per cent of which were light vehicles (cars, utes, vans, SUVs). That’s almost one per person and more than one per licenced driver (there are about 3.6 million). Depending on which study you look at, we have the highest rate of vehicle ownership in the world, having recently overtaken the United States, which had been the world leader for years.

The average age of our light passenger fleet is now 14.7 years, the oldest since records began in 2000. This is older than any country in Western Europe — the European average is 11.8 years — and older than the US (11.8 years), Australia (10.4 years), Canada (9.7 years) and the United Kingdom (8.8 years).

Our vehicles are also big, meaning they are typically less fuel efficient and belch out more carbon dioxide than cars in most other countries. The average engine size is 2274cc, a figure only pipped by Australia, the US, Canada and, interestingly, the Philippines.

This has all contributed to the outsized role of road transport in our greenhouse emissions. The sector now makes up 19 per cent of our greenhouse emissions and almost half of our carbon emissions from fossil fuels. Transport is also our fastest growing source of emissions. They nearly doubled between 1990 and 2019 and are now fifth highest per capita in the OECD, behind Luxembourg, US, Canada, and Australia.

How did we get here?

Auckland’s Queen Street in 1977 was mostly filled with cars assembled in New Zealand. Photo: Alexander Turnbull Library.

Made in New Zealand

New Zealand has long had a lot of cars. According to the national encyclopaedia, Te Ara, in 1929 one in 10 New Zealanders owned a vehicle, a rate second only to the US. This was down to our geography, according to Te Ara. Cars were “the ideal transport solution for New Zealand’s small rural population, dispersed over a relatively large land area with rugged terrain”.

Initially our cars came from Britain and the US, but we soon started assembling them here. In 1922, the Colonial Motor Company built the country’s first specialised assembly plant in Courtney Place in Wellington — it was the capital’s tallest building at the time — assembling Fords. The industry was supported by government tariffs, and later import licences, which made importing cars expensive and the industry boomed. The industry hub was Lower Hutt, where General Motors cars were assembled — Chevrolets, Pontiacs, Buicks, Oldsmobiles — and later Fords and Holdens, but there were plants right around the country. Morris cars and Hondas were built in Auckland; Fords in Timaru, Triumphs and Hondas in Nelson; Renaults, Peugeots, Fiats, Datsuns and Toyotas in Thames; Dodges and Toyotas in Christchurch; Suzukis in Whanganui; and Mitsubishis in Porirua.

General Motors Petone plant in 1957. The plant opened in Lower Hutt in 1936 and vehicles were made there until 1988. Photo: Alexander Turnbull Library.

Import restrictions, however, meant they struggled to meet demand. When vehicle use boomed in the 1950s, people had to put their name on a waiting list to buy a new car, which could take months or even years, and even getting a second-hand car could be challenging. In the book From the Rising Sun to the Long White Cloud, which documents the history of the used-import industry, one dealer recalls about 30 used-car dealers lining up on the front lawn of a house in Mount Roskill in the 1960s after the resident listed a single Mini Cooper for sale.

Clive Matthew-Wilson, editor of the car buyers’ guide, Dog and Lemon, worked as a mechanic in the late 1970s and early 1980s and owned a garage on Ponsonby’s Franklin Rd. He says the standards of New Zealand-assembled cars was variable and, overall, the fleet was appalling.

“It would be perfectly normal for students with no experience to get a job in a car assembly plant for the school holidays and the quality you got was largely a lottery,” Matthew-Wilson says. The kits we assembled also tended to be very basic but, because the supply of vehicles was so constrained, cars were very expensive and older vehicles were painstakingly kept on the road. “If you wanted an affordable car in the 1980s you’d be driving an old Morris Minor with no crash standards whatsoever and the brakes were mainly symbolic,” Matthew-Wilson says.

Waka Kotahi NZ Transport Agency policy advisor Iain McGlinchy recalls that he could see the road through a hole rusted through the floor pan in his first car, a 1967 Peugeot 404 built in Thames, which he bought in 1986. “No one thought that was unusual,” he says.

The local assembly industry peaked in 1982, when more than 120,000 vehicles were assembled. Within a few years the industry was decimated and the vehicle fleet was transformed.

The first used Japanese cars imported into New Zealand are believed to be a Mitsubishi Starion, shown below, and a Toyota Supra brought in by rally driver and car dealer Garry Cliff in 1986. Photo: Gary Cliff.

The Genesis of the Used Import

The revolution began by accident. In 1986, Christchurch car dealer and rally driver Garry Cliff went to Japan to buy a couple of rally cars. Because the cars wouldn’t be registered or driven on public roads they weren’t subject to import restrictions. But when the vehicles arrived in New Zealand and went through customs, he was informed that the rules had just changed and he could register the cars immediately. Previously, people were allowed to bring back one car with them from overseas provided they used it in the country of origin for three months. But in August 1986, that rule was abolished and you only had to have used the vehicle in the country — a definition vague enough to create a loophole.

Cliff, who had been a car dealer since 1973 (he still owns Magnum Prestige in central Christchurch), saw the opportunity immediately. Japan had a glut of used cars because of the country’s expensive and stringent Shaken test, an inspection carried out every two years which effectively makes it uneconomic to keep many seven-year-old vehicles on the road. Japanese used cars were also far better than those in New Zealand, with mod-cons like air conditioning, ABS brakes and power steering that many Kiwis had never seen.

“The cars were half the price and with half the mileage than what you’d get in New Zealand, and far better quality,” Cliff recalls.

Within three months he had signed up a group of prospective mum-and-dad buyers from Christchurch and flew them to Japan as a test run. He took them to Tokyo car yards where couples could buy one car for themselves and one to sell through Cliff’s business back in Christchurch. The first trip was a success and the “baggage car” used-import trade was born. Cliff soon had a six month waiting list for the buying trips and would book 80 seats on every flight between New Zealand and Tokyo — a service that only ran once a week on Saturdays. Cliff’s seminars advertising the trips were so popular he had to start holding them in the Christchurch Town Hall. He later realised he could pay Air New Zealand flight crew who worked the Auckland-Tokyo route to use their passport details to import vehicles as well.

Within months the car market in the South Island had transformed and dealers around the country began copying his business model. Some offered free trips to Japan in exchange for using travellers’ passports to import cars, and others imported vehicles salvaged from the scrapheap — they were still better than second-hand cars in New Zealand.

Garry Cliff’s Christchurch car yard became the epicentre of New Zealand’s used Japanese imports in 1987 after he discovered a loophole in the country’s import restrictions. Photo: Garry Cliff

The government soon started issuing import licences allowing people to import used cars without flying across the Pacific. The new vehicle importers and car assembly industry fought the change, but the government went even further. While other countries like the United Kingdom and Australia continued to restrict used imports to protect local car manufacturing, in the late 1980s the Labour government abolished vehicle import licences and duties entirely and tariffs were phased out.

Imports skyrocketed and prices declined. In 1985 there were fewer than 3000 vehicles imported into New Zealand, new or used, but by 1990 that had grown to 85,000, 53 per cent of which were second-hand and almost entirely from Japan. The vehicle assembly industry meanwhile was decimated. The last plant, Porirua’s Mitsubishi factory, closed in 1998, the year the last import tariffs were removed.

At first, the fleet size didn’t increase and the average age reportedly decreased as used imports drove the old Morris Minors and Hillman Hunters off the road. But by the mid-1990s the fleet started growing again.

Iain McGlinchy probably knows more about New Zealand’s vehicle fleet than anyone else. Before joining Waka Kotahi in February, he spent 17 years as a policy advisor at the Ministry of Transport, helping compile its vehicle fleet statistics. McGlinchy says almost everything that people believe about the country’s vehicle fleet is wrong, or unimportant. He says the introduction of used-imports was one of the best things that happened to the fleet. Our cars were so old and basic that importing used vehicles actually improved the quality.

“We got much newer and safer vehicles,” he says. “Until about 2005, the used cars were better on every level than a New Zealand-new one because we were able to cherry pick the top-spec ones from Japan.”

Gradually, however, our vehicles got older. Partly this is down to two large peaks in the age of our used imports — in 1996 and 2005 — caused by the introduction of a safety standard introduced in 2001 and an emissions rule in 2012, which prevented vehicles manufactured earlier from being imported. As the fleet aged, those two humps have dragged up the average age of the fleet. There are still 90,000 cars from 1996 on the road (including my Sentra) and 260,000 from 2012.

McGlinchy says countries with younger vehicle fleets tend to be richer and have a land border with a poorer country that they can sell their old cars to, or they salt their roads in icy winters, which shortens the lifespan of their vehicles.

Our older cars are also not necessarily worse for the planet, he says. Over time, vehicles have become significantly heavier and with larger engines, meaning newer cars aren’t much more efficient than cars from the 1990s. For example, my Sentra weighs about 20 per cent less than a 2020 Corolla hatchback, while the engine is 20 per cent smaller. According to the government’s Right Car website, the emissions from a 2001 Honda Civic are actually eight per cent lower than the 2021 model.

Iain McGlinchy says, while new cars are safer, the majority of road deaths are caused by drivers “on rural roads, at night, not sober”, and vehicle design has little impact on this. “If you’re driving in a city sober at slow speed in daylight you are really, really safe in almost any vehicle.”

Overall, vehicle fuel efficiency has improved by 30 per cent since 2005, but this is based on vehicle testing in a controlled environment. McGlinchy says real-world emissions figures show much more modest gains, suggesting manufacturers have simply got better at passing the tests rather than actually reducing emissions. Real-world fuel efficiency, based on the country’s total petrol consumption divided by the kilometres travelled in the fleet, has improved at a far more modest rate – about 0.5 per cent a year. Although McGlinchy says the latest testing regime is more accurate.

New vehicles are also driven a lot more than older vehicles. As a consequence, having a younger fleet wouldn’t necessarily reduce our transport emissions on its own.

“A brand new vehicle travelling 17,000 km a year is going to be much worse for emissions than a 20-year-old vehicle travelling 4000 km a year.”

New cars are definitely safer than older cars, McGlinchy says, but the difference isn’t as dramatic as people think. A Monash University study found a person in a 1996 vehicle had about a 17 per cent risk of being injured in a crash compared to about a 12 per cent risk in a 2016 vehicle. However, it found older vehicles aren’t any more likely to be in a crash. Heartening news for my Sentra. Although McGlinchy says this is also changing with the introduction of active safety technology, like automatic emergency braking.

But then why have our transport emissions almost doubled since 1990? Simple, McGlinchy says. “It’s because the size of the vehicle fleet doubled.”

Since 2000, the number of vehicles has increased 62 per cent (the total distance travelled by the fleet each year has increased by a more modest 26 per cent). For this, the used import can probably shoulder some of the blame, for making vehicles so cheap.

We also have a penchant for larger vehicles. The average engine size increased by 10 per cent between 2000 and 2010 to 2291cc and has declined by less than one per cent since.

McGlinchy says this is largely because people tend to buy vehicles for the recreation they think they might do – to reach a tramping track or tow a boat – rather than the trips they mostly do, like driving to the supermarket or the daily commute.

“If we had brought in a fuel economy standard 10 or 15 years ago it might have been a different story, but Steven Joyce [the transport minister from 2008 until 2011] said we didn’t need one. It set everything back a decade.”

Now we are attempting to catch up.

Karangahape Road in the late 1970s. Photo: Basil Willians, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections.

Turning the Oil Tanker

In 2020,New Zealand burned about 800,000 tonnes of coal at Huntly Power Station to keep the lights on during a dry year when the lakes were low. That may sound like a lot, but we actually have one of the greenest electricity supplies in the OECD. Last year only Iceland, Norway and Greenland had greener power and two of those countries have a population smaller than Christchurch. In 2020 the sector was responsible for six per cent of New Zealand’s greenhouse emissions. Transport, by contrast, was responsible for almost triple that.

University of Canterbury professor David Frame has been a lead author for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and says transport is one of the most important sources of emissions for New Zealand to address. Unlike most other countries, we don’t have a lot of heavy industry and coal power stations that we can shut down to reduce our carbon emissions. “We have to address transport emissions if we are serious about climate policy, but we’ve put no meaningful pressure on the sector for the last 30 years.”

Changing the vehicle fleet is no quick task. Iain McGlinchy likens it to turning an oil tanker. On average, our cars are 19 years old when they’re scrapped so it will take at least that before the high-emissions vehicles entering the fleet now are gone.

The government wants 30 per cent of the light fleet to be zero-emissions by 2035 — in 2020, the proportion was just 0.44 per cent. To achieve this it has announced a three-pronged programme. The first policy, the Clean Car Discount, or “feebate” scheme, was introduced in July last year. Vehicles that emit less than 146 grams of CO2 per kilometre (CO2/km) can get a rebate of up to $8625 for a new vehicle and $3450 for a used import (for reference, a 2020 Honda Civic emits 158g CO2/ km). On the flipside, from April this year, vehicles that emit more than 192 g CO2/km get hit with a fee of up to $5,175 for a new vehicle and $2,875 for a used import.

Alongside this is the Clean Car Standard which sets a sinking lid on the average fuel efficiency of vehicles imported into the country. Starting from next January, vehicle importers will pay a fee if the average emissions of the vehicles they import are above government targets. Last year, the average vehicle emitted 169g CO2/km but by next year the average will need to be less than 145 g CO2/km or the importer will have to pay a fee for every gram of CO2 they exceed the target by. The targets also ramp up rapidly. By 2027, the average emissions of the imported fleet will need to be less than 63.3 g CO2/km to avoid a fee, about the same as a plugin hybrid Prius and less than a Corolla hybrid. The fee for missing the targets will also rise. By 2027, if a dealer imported 100 new cars at the current average of 169 g CO2/km they’d be liable for a $713,475 fee – more than $7,000 per vehicle.

While the full suite of policies hasn’t come into effect, the fleet is already changing. In the 12 months to March, electric vehicle (EV) imports more than tripled and made up almost 9 per cent of market share in that month, up from 0.2 per cent in March 2017.

The figures sound impressive, until you remember there are 3.36 million light passenger vehicles in the country. Last year, the most popular new vehicle was the Ford Ranger ute. In fact, eight of the top 10 new vehicle models sold last year were utes or SUVs — the other two were the Toyota Corolla and Tesla Model 3. The fleet is also still growing. In 2020, the fleet increased by more than 20,000 vehicles, with 175,241 light passenger vehicles deregistered — presumably scrapped — and 195,486 vehicles newly registered.

The third policy may have my Sentra in its sights. The government announced in May that it’s planning to spend $569 million paying people to take their old vehicles to the wreckers. It will be funded by proceeds from the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) and will start with a $31.812 million trial next year. About 2500 low-to-middle income car owners will get a grant to scrap their old and inefficient vehicle and either buy a new low-emissions car or e-bike, or get public transport vouchers.

The details haven’t been released yet, so it’s not yet clear which vehicles will be eligible under the scheme or how much people will get, but the trial’s budget equates to $12,724 per vehicle. A ministry spokesperson said this was expected to reduce transport emissions by between 0.2 and 1.8 tonnes per vehicle, the equivalent of driving a car between 1242 km and 11,180 km. By contrast a carbon credit, which represents one tonne of CO2, costs about $86.

The policy has been broadly supported by the auto industry, although some would like to see the grant available for all New Zealanders. But it has few fans among climate-change experts. Overseas, scrappage schemes have primarily been used to support domestic car manufacturers during economic crises and there’s not a lot of evidence that these schemes result in significant emissions reductions. Climate Change Commission (CCC) chair Rod Carr told Newsroom that similar schemes implemented overseas had been “relatively expensive ways of reducing emissions” and it would need to be carefully designed.

Victoria University of Wellington adjunct professor Ralph Chapman has been working in climate change policy since 1988 and has co-written a number of papers on how the government could reduce transport emissions. He says it’s a flawed scheme.

“I’ve always thought they’re evidently bad schemes,” Chapman says. “By scrapping an old vehicle and replacing it with a new vehicle, you’re inducing a whole lot of emissions during the manufacturing and shipping of the vehicle. Every time you buy a new car, you are causing a lot of emissions to be released.”

The emissions from manufacturing a vehicle are estimated at about 5.6 tonnes of CO2, the equivalent of driving an average vehicle 33,136 km. Consequently, the more kilometres a vehicle drives, the lower these emissions will be per kilometre over its lifecycle.

Chapman says increasing funding for public transport would be more effective. In April the government halved the price of public transport fares, but the subsidy runs out at the end of January and would cost between $100 and $160 million a year to continue.

Massey University distinguished professor Robert McLachlan says, despite the large price tag, the scheme will only result in a small change to the fleet. If the grant was $12,000 per vehicle and the entire budget was spent on grants then it would result in 47,416 vehicles being taken off the road. By contrast, there were 12,580 Ford Rangers sold in New Zealand last year, and 8430 Toyota Hiluxs. “I don’t see how it can scale up to impact the emissions of the whole transport system.”

In a report released to North & South under the Official Information Act, transport officials acknowledged that “the emissions reductions [from the scheme] are expected to be small” but that “social-equity benefits are the main focus of this policy”. As the price of carbon credits increases in the ETS, fuel prices will go up, disproportionately impacting those on low incomes who can’t afford more efficient alternatives.

However, Chapman says a better way to address equity issues would be to simply use the proceeds of the ETS to pay a grant to those on low incomes. The ACT Party has advocated for a similar policy.

Vehicle-emissions consultant Gerda Kuschel is an advisor to Waka Kotahi and the Ministry of Transport and would like to see initiatives that ensure vehicles already in the fleet are operating as efficiently as possible. If warrants included an inspection to ensure that tyres are fully inflated and the oil has been changed regularly, she says that could have a significant impact. “It’s not sexy, but it’d be quite effective.”

But if we do decide to accelerate vehicle scrappage, she says we also need to invest in dealing with the waste that will arise from disposing tens of thousands of vehicles. “We need to ensure we are not turning a greenhouse emissions issue into a solid waste issue.”

Old cars, left, stored inside the former Burnside freezing works in Dunedin, waiting to be stripped for parts at Eco Auto Recyclers. Photo: George Driver.

Where Our Cars Go to Die

For 126 years, thousands of animals went to Burnside freezing works in Dunedin to be slaughtered before their carcasses were shipped around the world. Now the cavernous concrete buildings of the abattoir are where cars go to die.

The freezing works houses four auto wreckers, including Eco Auto Recyclers, which takes up the bottom two floors of the enormous grey building. Out front I find a snapshot of New Zealand vehicles over the last 30 years, stacked two high. There’s a late model Mini Cooper teetering on top of a 1990s Corolla; a dismantled cab of a Toyota Hilux atop a Subaru Legacy. There’s even a Domino’s Pizza minivan.

The business gathers old vehicles from farms and garages around the lower South Island and brings them here to be stripped for parts. Manager Andrew Stevens explains that most parts of a vehicle can be salvaged and reused. They try to salvage as much as they can for the domestic market, but there’s also a growing export market for old car parts. Out front, Stevens shows me a dozen “half cuts”, vehicles that have been sliced through at the driver’s seat so only the front half remains which contains its most valuable parts. These carcasses are destined for Dubai, he says. The country has become a conduit for old cars and parts destined for Africa. Last year New Zealand exported $55.6 million worth of car parts and accessories worldwide, mostly to Australia.

Once a car is stripped it is drained of oil, which is sold to Fulton Hogan and used in making tarseal. The used tyres are chipped and shipped to India to be recycled. The batteries, however, have become a burden. They also used to be sent overseas, however business owner Chris Robinson says container ships won’t take them any more due to the high risk from the battery acid. While battery recycling plants have opened in Auckland, it’s difficult to get the batteries there from Dunedin for the same reason. At the moment, he sends them to Christchurch where a business has a warehouse filled with old batteries.

“They don’t know what to do with them and now they don’t want any more,” Robinson says. So then what happens, I ask. “You tell me,” he says, hands in the air in frustration, beside a stack of dozens of old batteries.

Once stripped, the vehicle shells are taken down the road to Otago Metals in Green Island where a crane lifts them into a crusher and they’re cubed. The cube is trucked to a scrap metal processing plant in Christchurch where it’s shredded and sorted into steel, non-ferrous metals (like aluminium and copper) and waste, including plastic and furnishings. Some scrap steel used to be recycled at the Glenbrook steel mill in Auckland but they won’t take scrap metal any more and now it’s all shipped overseas. The nonferrous metal is also exported while the waste ends up in landfill.

For an industry processing about 175,000 vehicles a year — and the toxic waste that comes with them — it’s currently surprisingly unregulated.

Adele Rose runs a company that develops product-stewardship programmes and says compared to other countries, we are “massively behind” in tracing and recycling vehicles at the end of life. “There’s been a bit of a ‘she’ll be right’ opposition to regulation,” Rose explains.

At the moment we don’t know to what extent vehicle parts end up in landfill and how much of a vehicle is reused or recycled. Other countries have had stewardship schemes for decades, where a fee is added when vehicles are first registered to ensure they are recycled. The European Union has had a stewardship scheme since 2000.

Rose has spent the last decade trying to establish a similar scheme here and was a founding member of Auto Stewardship New Zealand (ASNZ), a charitable trust that aims to do just that.

The group’s initial focus has been car tyres. Around 6.5 million used tyres reach the end-of-life in New Zealand each year and about 40 per cent end up in stockpiles or landfill. Over the past decade, ASNZ has been working to get a small fee added to tyres when they are imported to fund a tyre recycling programme. A tyre stewardship scheme will finally be launched next year after receiving government funding. About half of the country’s used tyres will go to Golden Bay Cement, which will use them to fire its cement kilns in place of coal, and as an ingredient to manufacture the cement. Where the remainder will go is still being determined, but will likely be processed into other rubber-based products.

The group then plans to develop a stewardship scheme for ensuring the refrigerants in air-conditioning units, a powerful greenhouse gas, are disposed of properly. Then a battery stewardship scheme will be introduced. Finally, the group plans to develop a whole-of-vehicle stewardship scheme. Rose says a $120 levy could be charged when vehicles are first registered in New Zealand and this could fund a programme to track vehicles when they are deregistered and ensure they are reused and recycled to the greatest extent possible. The small fee helps make recycling the materials economic, while having a centralised body managing the process creates a guaranteed supply of materials for business, giving them confidence to invest in the expensive plant required in recycling. She says, with government support, she’s optimistic a scheme could be up and running in two or three years.

“We’ve got a pathway now, we’ve got a willing industry and there’s government funding.” A Ministry of Transport spokesperson, however, says it hasn’t committed to funding a vehicle-stewardship scheme yet.

The Electrifying of a Honda City

The tide is out at Blueskin Bay, north of Dunedin, when Rosemary Penwarden takes me for a drive in her 1993 Honda City. As we head down the northern flank of Mt Cargill and into Waitati, I can hear the sound of the tyres on the road and the wind whistling off the old car’s boxy bonnet, but otherwise it’s silent. Penwarden tells me this 29-year-old vehicle is the future.

Two years ago, the retired medical lab scientist and Oil Free Otago activist began converting the used Japanese import into an EV It took about eight months and cost around $24,000 — about the price of a five-year-old Nissan Leaf. Pendwarden says she did it to show another way is possible and believes if EV conversions are done at scale, using kit sets for popular models, it could be a less wasteful way to transition the fleet.

“The world has too much stuff already,” she says. “We’ve got to use what we’ve got.” She’s not the only one. A decade ago, James Hardisty converted a 1975 two-cylinder Daihatsu Max into an EV in Dunedin. He’s now completed about 15 conversions out of a workshop in North East Valley — his latest project is converting a 1983 Toyota Hilux. He says bigger vehicles like utes are ideal to convert as they produce more emissions and there are currently few alternatives — the first commercial EV ute is expected to go on sale in New Zealand this summer. His business partner converted a 1994 Toyota RAV4 about 12 years ago and it’s still going.

At the moment, the cost of conversions is prohibitive, except for classic vehicles and passion projects. But as battery prices come down, Hardisty believes it could become more viable, particularly for high-polluting vehicles.

“We are going to have a lot of old utes. Surely it’s better to repurpose the vehicle by installing an electric drive system and give it a new life, rather than manufacturing an entirely new vehicle.”

A Ministry of Transport spokesperson said imported vehicles can receive the Clean Car Discount if they are converted to EVs before they are registered in New Zealand, but at the moment there’s no funding for converting cars that are already here.

“This is something that could be looked at in the future as the market develops.”

Rosemary Penwarden spent eight months and $24,000 converting her 1993 Honda City into an electric vehicle. Photo: George Driver.

James Hardisty has converted more than a dozen vehicles to become electric. His latest project is a 1983 Toyota Hilux. Photo: George Driver.

The Fate of a Nissan Sentra

After we bought the Subaru Impreza last year, the Sentra ended up under a tarpaulin in a vacant section beside our house for a year. Last month I peeled off the cover. As I reinstalled the battery I noticed a worm living in a pile of composting leaves under the bonnet, but the car still started first time. On the drive to Dunstan Motors, the car wallowing on soft tyres, I experienced a flood of nostalgia along with that familiar feeling of dread, the pre-warrant anxiety that a generation of New Zealanders know well.

I need not have feared, the Sentra flew through. But I’m still not sure what I should do with it next. There’s no simple answer. Iain McGlinchy says my new Impreza won’t necessarily be any better for the environment than driving the Sentra. Robert McLachlan says scrap it — having one fewer car in the country can only be a good thing for the environment. Adele Rose also says scrap it, then she confesses to driving a 20-year-old Toyota Aurion “which should be scrapped”. “And yet I don’t want to give that up and I’ve done 370,000 km in it.”

Like Rose, I’m completely unable to make a rational decision about the future of my vehicle. My mechanic, who I bought the car off, suggests I park it out front of the garage on Clyde’s main street with a For Sale sign in the windscreen, back where I first set eyes on it nine years ago. So, motivated with more than a little self-interest, that’s where it will go. Out for one more round of the pass-the-parcel of New Zealand’s secondhand car market, until the music finally stops and it’s dismantled, melted down and shipped offshore.

George Driver is North & South’s South Island correspondent. This role is made possible by support from NZ On Air’s Public Interest Journalism.

This story appeared in the November 2022 issue of North & South.