Culture Etc.

Raoul Schwing, above with members of his kea flock, took over as head of Haidlhof’s Kea Lab in 2016.

A Foreign Flock

How did a small spa town in Austria end up with the largest collection of kea in captivity — and what is it doing with them?

Story and photography by Gregor Thompson

I count six olive-green parrots pacing in front of me, each one sizing me up. They’re larger than I would have expected. Looking down at my pair of borrowed gumboots I slowly swivel my head, trying not to make any sudden movements. Behind me to my left, I sense an intrigued resident ogling my potentially comfortable shoulder. They seem like they’re plotting something. A man in cargo shorts assures me they are simply making my acquaintance.

Despite trips to the South Island as a kid and a modest amount of southern-alpine action as an adult, this is the most I have ever interacted with New Zealand’s native parrot. Funny that it should happen in Austria, half a world away from our mutual home.

Bad Vöslau, a town of around 12,000 people 35 kilometres south of Vienna is, at least on the surface, your typical Austrian setting. In the summer, its two-storey redbrick homes are hidden among lush green foliage, emerging briefly in autumn as the leaves fall before being buried again beneath wintertime snow.

If Bad Vöslau is known for anything, it would be its natural thermal baths and the town’s proximity to the Merkenstein Ruins — the remains of an ancient castle that Ludwig van Beethoven once wrote a couple of songs about. Two kilometres east of the ruins is the old but still intact “Meierhof” of Merkenstein Castle. Meier, a common surname in the German-speaking world, marks the descendants of the old administrators of noble or ecclesiastical estates. In feudal society, Meiers made sure plebs paid their landlords. Meierhofs are where they lived.

Today, instead of being occupied by tax collectors and bailiffs, the Meierhof is the location of the Haidlhof Research Station, an animal-research facility which holds, among other species, 26 New Zealand kea — likely the largest number kept in captivity anywhere in the world.

Run collectively by the University of Vienna and the University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna, Haidlhof was officially established in 2010. Scientists from all over the world come here to research the intelligence of animals, focusing on the behaviour and cognition of birds and mammals as well as their intercommunication and bioacoustics (roughly meaning how animals make and perceive noise). The facility is also part of a holistic conservation effort for kea, whose current wild population sits somewhere between 3000 and 7000.

The man in the cargo shorts telling me not to worry is Raoul Schwing, head of Haidlhof ’s Kea Lab, where his circus of kea (yes, that is the collective noun) lives in an enormous mesh-walled aviary 4 metres tall, 10 metres wide and 52 metres long. Schwing thinks it’s the largest solely research-focused aviary in the world. Inside, it’s furnished with all the essentials: posts to perch on, swings to swing on, trees to gnaw on, beams to balance on, ponds to swim in and toys to play with. One such “toy” is a contraption Schwing and his colleagues fashioned that distributes food only if four separate kea pull on four separate small chains at the same time — apparently they worked that one out pretty quick (and are still the only non-human animals known to have done so).

Originally from Canada, Schwing began his work with kea after earning his PhD at the University of Auckland, focusing on the birds’ communication and trying to understand it. He has now worked with the entemic South Island alpine parrots for more than 13 years. Unusually intelligent and curious, kea are an excellent breed to study as they possess what Schwing calls “context intelligence”, meaning they adapt rapidly and comfortably to new environments.

Incidentally, it was Schwing who first found Bruce, a kea at Christchurch’s Willowbank Wildlife Reserve who hit the headlines internationally in 2021. Schwing came across Bruce as a halfbeakless fledgling still living with his parents on Deaths Corner near Arthur’s Pass in 2013. Bruce may as well have been living on death row — once he left the nest he would have been totally incapable of feeding himself. Knowing this, Schwing immediately took him in; within 24 hours Bruce was eating out of Schwing’s wife Amelia Wein-Schwing’s hand. In time Bruce learned how to make up for the missing top half of his beak, including using pebbles to preen himself – a skill that earned him all that publicity.

Raoul Schwing was born in Germany but grew up in Canada, moving to Austria following a stint spent studying in Auckland.

Before I arrive at Haidlhof, Schwing details some precautionary measures. “Anything you bring into the aviary can, and often will be ‘explored’ by the kea,” he warns me. This means holes bitten into fabric, even leather. He adds that the facility also has a couple of very cheeky birds that might go for some flesh — not out of malice, but rather fierce curiosity. Highlighting the fact he still has all his fingers, Schwing assures me there’s nothing too much to worry about.

Most striking when you enter the enclosure is how tame and comfortable these birds are around humans. Hopping over awkwardly, they’ll confidently ask what your business is as best they can, ignore the answer and proceed almost immediately to climb all over you. Anything with an edge is fair game: the top of my gumboots, the lower hem of my shorts and my camera all became objects to attach themselves to. Despite their ostensible conniving, the kea are not remotely vicious, only playful. The problem is they want to play using their sharp talons and powerful beaks.

Schwing recognises and differentiates each bird as their father might, not only by appearance but by behaviour. Some are timid, others adventurous; some are nimble, others clumsy.

One, Diana, tends to get herself into life-threatening situations. At just a week old, when she was gaining strength in an incubator after a complicated birth, Diana managed to push her tiny and still-soft beak through a mesh grate and into a ventilator fan. Diana is now five years old and perfectly healthy. Another bird, Pick, has earned the title of “resident gourmet”, due to being the only kea that sniffs things before he eats them. The birds’ nostrils (otherwise called “nares”) are located high on their beak, so Pick has to bend quite far forward in order to get a good sniff.

Despite their ostensible conniving, the kea are not remotely vicious, only playful. The problem is they want to play using their sharp talons and powerful beaks.

The work Schwing oversees at Haidlhof varies from understanding kea society and their nature to assessing their capacity to cooperate and problem-solve. In one paper Schwing co-wrote, titled “Kea (Nestor notabilis) Decide Early When to Wait in Food Exchange Task”, the scientists demonstrate that kea will patiently wait and pass up a snack when they know a tastier or larger snack (peanuts instead of pellets, for instance) will be awarded to them if they do so. This experiment showed kea are able to differentiate between foods and that they will wait longer for items they prefer — an ability humans develop around the age of four.

All of this is fascinating stuff, but a key question remains: How did all these kea end up in Bad Vöslau in the first place?

The history of kea in Austria goes back as far as 1907. According to Malcolm Ross’s 1914 book, A Climber in New Zealand, Franz Joseph I, Emperor of Austria at the time, thought it would be a good idea to import kea, offering up the native European goat-antelope species of alpine chamois in return. Predictably, while chamois thrived in mountainous New Zealand without predators, the imported kea suffered in small cages. Some years later, on a trip to Europe, Ross paid a visit to the Emperor’s Zoological Gardens at Schonbrunn, noting only one bird had survived. “A sedate and venerable kea, and very sad he looked, confined as if he was in an ordinary parrot cage,” he wrote. Continuing, he recalls how “I said a few words to him in his own kea language, and he cocked his head knowingly on one side and eyed me curiously as if he had heard the sounds before but had forgotten them…”

This particular bird’s fate may have been similarly tragic had it stayed at home.

Birds were slaughtered in their native habitat because of their proclivity to attack and sometimes kill sheep — a punishment that did not fit the crime, as the accusation was severely overstated.

What’s more, the kea cull was state-sponsored. Between 1867 and 1970, severed kea heads or beaks were exchanged for cash rewards, sometimes fetching as much as $75 a beak in today’s currency. An estimated 150,000 birds were killed. Suffice to say that since kea met man, history has been hard on the bird; conservationists think it’s a miracle the parrot has not joined the moa and the dodo.

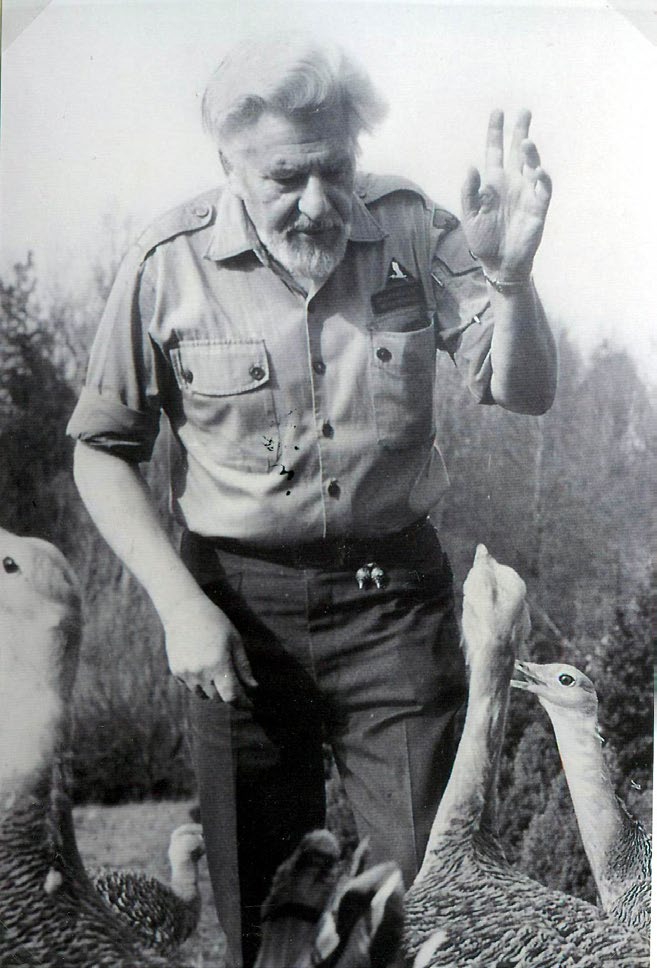

After avoiding an Austrian Emperor’s cruel curiosity and surviving a homeland onslaught, the original kea of Haidlhof have their own story to tell. Some are the direct descendants of two birds who ended up in the hands of photographer, zoologist and television personality Otto Koenig in the 1970s. Old photos of Koenig depict a broad-chested and grey-bearded man whose khaki and breast-pocketed shirt is worn tucked into his khaki and side-pocketed shorts. He looks like the kind of man that could both toss a fridge and tell you how it works. As for how exactly the kea got here, the prevailing theory is that they were smuggled semi-legally back in the days when no one had heard of biodiversity and the general approach to border control was anything goes.

Some of Haidlhof’s current kea stock descend from birds bred by the Austrian zoologist and TV star Otto Koenig — pictured here in 1987 with a drove of great bustards at Vienna’s Wilhelminenberg research station.

Little is known about how these early expatriate kea spent their time in Austria, although there were a few rudimentary studies conducted and they did apparently make it onto Austrian television a couple of times. One thing we do know is that in the first 13 years after arriving, they were incredibly successfully bred. In spite of some shoddy book-keeping, Schwing suspects the initial breeding program is the reason kea are so well represented in European zoos today.

Sadly, a deadly bout of the mosquito-borne West Nile Virus made its way into the flock some time after Koenig’s death, considerably depleting the original population. As a result, the current kea at Haidlhof are a motley crew of sorts, and while some have ancestry with Koenig’s original birds most of the current stock were bought off various private European kea breeders (yes, they exist). The others are the descendants of breeding between both groups.

At present, Haidlhof is working on understanding how effectively kea imitate one another. Imitation for human beings is a crucial aspect of development: we learn efficiently by constantly watching parents, siblings and peers perform tasks and then reproducing their actions. Consider the three-year-old boy shouting down a fake plastic telephone. To determine whether kea do this, tests have been undertaken and an article currently being drafted will be submitted for peer review in October. The experiment involves one specifically trained bird opening a complicated box as another kea — who is not familiar with the box — watches from behind a barrier. The observing bird will then get its own opportunity to open the box. Researchers at Haidlhof discovered that not only are the birds capable of imitating, they can also gauge principles; that is, copy the essence of the trained bird’s technique while experimenting where they can.

Queenstowner and chair of the Kea Conservation Trust Tamsin Orr-Walker — who knows Schwing well and visited Haidlhof in 2013 — greatly appreciates the work undertaken at the facility. She says it’s crucial, because learning how kea operate helps build an understanding of how they might prosper in their native environment. What’s more, conservation is a collective enterprise. “Even though they aren’t an Austrian bird, the work being done could help Austrian species. Any species for that matter.”

Unlike some of their distant parrot cousins, the kea has a relatively underdeveloped syrinx (or vocal organ). Instead of a “hello” or a desperate plea for a cracker, every morning Schwing is greeted by a characteristic chorus of chirps, rattles, whistles, trills, croaks and screeches. Though this might sound familiar to any regular listener of RNZ’s Morning Report, it’s a sound you wouldn’t expect to hear this far from the Southern Alps.

Asked what he finds most striking or exceptional about the kea, Schwing takes a while to think about it — it’s clear he doesn’t want to provide a disappointing answer. “It’s their tolerance,” he says after careful consideration. “If you introduce a new baboon to the troop, maybe, if it’s lucky, it is tolerated from a distance, and gets to spend the next several months on the margins, before actually joining the troop.” In the animal kingdom, when a new member is integrated, they need to fight for their position within the group, as hierarchy is crucial for maintaining peace and preventing constant anarchy.

For the kea, though, this doesn’t seem to be the case. They have developed their own — so far mysterious — way of structuring their society. With the exception of females in the breeding season, kea are exceedingly tolerant of one another, even if they have never met before. In five years of fieldwork, Schwing never once saw a genuine kea fight. When Haidlhof introduces an outsider, within three days the bird is seamlessly integrated into the flock. Indeed, if a new chick enters the group for the first time, other kea will subtly compete to make friends with it.

“They are just extraordinarily tolerant of one another,” Schwing says. “We humans could learn a lot.”

Kea can live for up to 50 years in captivity, significantly longer than the 30 or so years the birds have been known to survive to in the wild.

Gregor Thompson is North & South’s somewhat official European correspondent. He lives in Paris.

This story appeared in the November 2022 issue of North & South.