Our Man in Saigon

Civilian chaos, terror, advancing unfriendly forces: the fall of Saigon to communist troops was one of the defining final chapters in the Vietnam War. By late March 1975, many Western countries — who had backed the South Vietnamese — had shuttered their consulates and evacuated their nationals. New Zealand was no different. Now, an untold story of the nail-biting Kiwi departure — and the antics of a French fraudster — can be shared.

By Pete McKenzie

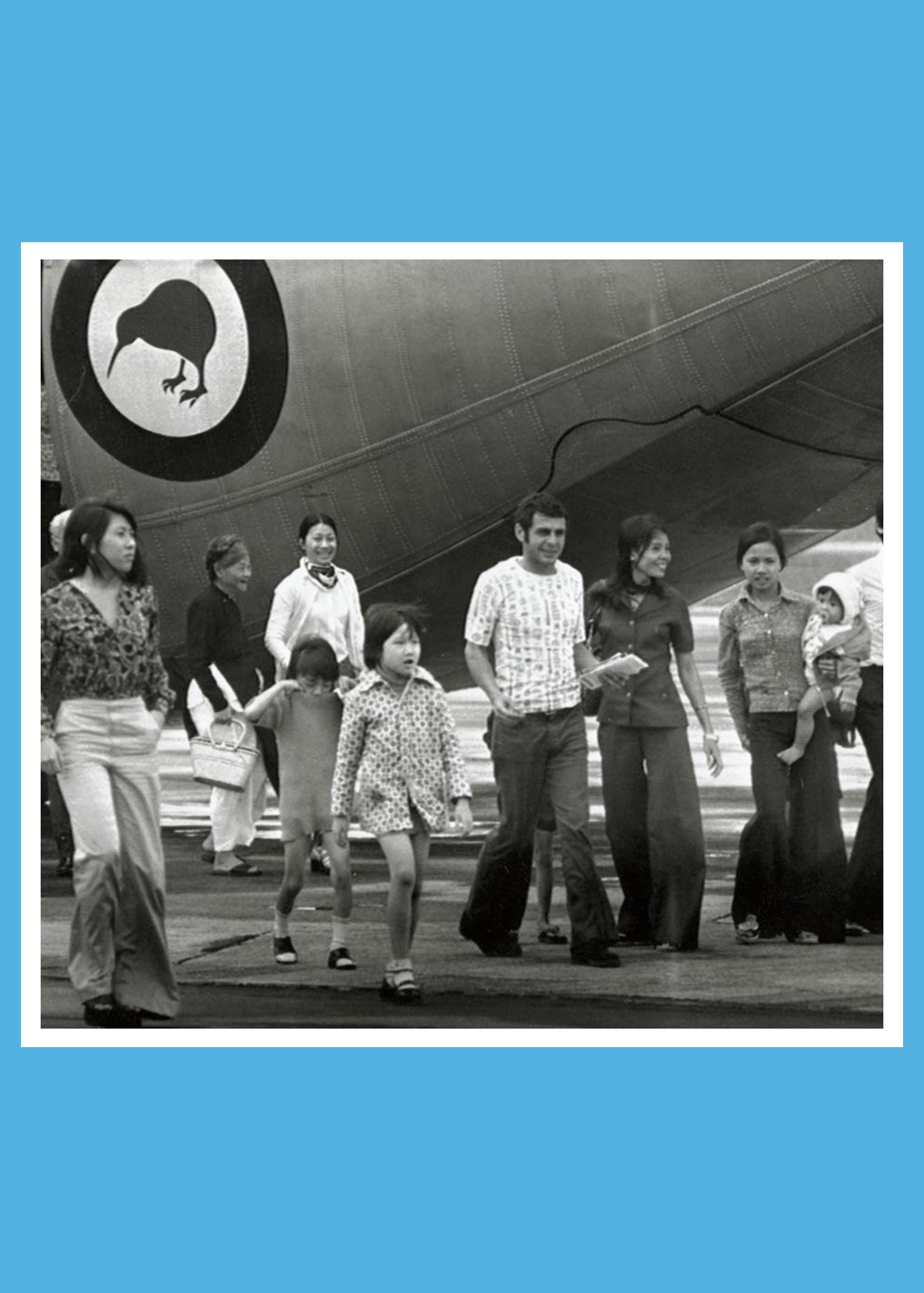

Evacuees from Saigon land on New Zealand soil at Auckland’s Whenuapai airbase, 23 April 1975.Photo: Alexander Turnbull Library.

As Frank Wilson nosed his station wagon between motorbikes and rickshaws laden with luggage, he planned what he would say if the soldiers he was driving towards opened the coffin in the backseat and found that the man inside was alive.

Outside the car, Saigon pulsed with anxiety. Thousands of people carrying small bundles of clothing hurried along on foot. Demoralised soldiers milled about on street corners. Frightened by intensifying conflict to the north, people had been fleeing the city for months. In March 1975, that flow became a flood. The North Vietnamese Army was advancing towards the city at a rate of 100 kilometres a day, and South Vietnam’s citizens and government were in a panic.

By now, the chaos was familiar to Wilson. He’d arrived in Saigon in 1973: it was his first posting abroad as a New Zealand diplomat. A slight man in his mid-20s with a shock of sandy hair, he looked like he was barely out of high school. But his youthful appearance belied a preternatural calm. One New Zealander who knew him says, “He was the kind of person who would never get in a panic.”

He was driving towards Tan Son Nhut Air Base, and New Zealand’s small Air Force outpost there: a collection of tents fortified against small arms fire by large bags of rice. If he could reach the tarmac behind the tents, New Zealand’s fleet of rickety Bristol Freighter cargo planes could ferry the “dead” man to safety.

The man had arrived in Wilson’s office towards the end of March, after South Vietnam’s government introduced compulsory conscription for military-age men. A Vietnamese national, he was the husband of a New Zealander: he asked Wilson to help him escape.

Wilson had already smuggled a few people in similar situations to the Bristols by bluffing his way through South Vietnamese checkpoints. But it terrified his boss, Kiwi ambassador Norm Farrell, who was sure the South Vietnamese government would be furious if they found out. Wilson explained to the man that he wasn’t sure he could take that risk again.

The man’s mind churned. An idea clicked into place. He would construct a box, bring it to the New Zealand Embassy in the centre of Saigon and clamber inside, while Wilson took over as driver. If the troops peered in, they would see a coffin — hardly an appealing thing to search.

Wilson couldn’t help himself. The idea was too exciting not to try. A few days later, he burst out of the embassy in the station wagon. There was only one safe route to Tan Son Nhut, and “safe” was a relative term.

On a previous trip, gunfire had spattered around Wilson’s vehicle and a helicopter had clattered overhead”as he drove out of a protective warren of low-slung houses toward the airport gates. “I was just so confused. There were a lot of gunshots around town anyway,” says Wilson. He had accelerated through the strafing and into the airport compound. “I soon realised they weren’t actually shooting at me.”

This time, as Wilson manoeuvred past American jeeps and the ancient blue-and-white Renault taxis that were a hangover of French rule, he hoped his passenger had brought cash. If they were caught, a few hundred American dollars might convince the guards to look away. If not, he couldn’t predict what would happen.

When they reached Tan Son Nhut, Wilson watched the guards for any signs of suspicion. But with their city collapsing around them, they had bigger things on their mind. They waved the car through.

He sped to the New Zealand outpost and parked in a spot out of view of the sentries. He opened the box, shook the man’s hand, and watched as he was hustled into the nearest Bristol Freighter.

Then Wilson got back in the car and returned to work.

The end of the Vietnam War was anarchy. The swift advance of the North Vietnamese was unexpected, as was the speed with which South Vietnamese forces collapsed before them. There was little time to make plans. It took just two months from the first North Vietnamese breakthrough for Saigon to fall.

Our collective memory of this moment is largely American, thanks to their dominance of the newsreel and media images of the day. A woman throwing her new-born child over a barbed-wire fence to reluctant United States marines. An American helicopter perched on a narrow roof, waiting as a CIA employee ushered up a ladder far more refugees than could fit in the aircraft.

But America was not the only Western power that struggled with the end of a war into which it had ploughed men and money. Hundreds of foreign diplomats raced to salvage something from the wreckage. Among them was Wilson, who — along with a handful of other New Zealanders — was charged with evacuating the last Kiwi doctors, journalists and aid workers from the nearly fallen city.

They succeeded to a degree that surprised everyone —”including their own reluctant government. Prime Minister Bill Rowling was told the final New Zealand flight from Saigon on 21 April would have eight passengers. It carried 33.

Their focus on New Zealanders had a cost, however. While a few dozen Vietnamese citizens were flown out of the country (under false pretences, in the cases of 10-plus male partners of New Zealand citizens), many Vietnamese supporters of New Zealand and refugees seeking asylum were left behind.

In the days that followed the New Zealand evacuation from Saigon, a handful of local staff continued to use the embassy radio, pleading for help from a country that had abandoned them. And when they finally scarpered, unaided, a French charlatan took over, parading through the streets of newly christened Ho Chi Minh City in the embassy car, proclaiming himself the new New Zealand ambassador.