Culture Etc.

Out There

A semi-industrial suburb in Auckland is home to a small museum with pieces of herstory so hard to find that it’s become a source of information for researchers from around the world.

By Gabi Lardies

If you walk down Bentinck St, in a semi-industrial part of Auckland’s New Lynn, you will find two used car yards, a tyre shop, a panelbeaters, and — flying proudly in front of a brutalist commercial building — a rainbow flag.

The coordinator of what’s thought to be the world’s only museum solely dedicated to lesbian history is today wearing black jeans with a collared black-and-white plaid shirt. “The building is not too bad,” Sarah Buxton says. “We’re just not in a very good location.”

Buxton and I chat on the first level of the Charlotte Museum, surrounded by a poster collection which is in the middle of being catalogued. On the ground level, two rooms hold the museum’s collections. Upstairs are two more small gallery spaces, as well as a library, an office, a work area for sorting, digitising and storage, and a dark room filled with archive boxes.

If the museum had premises near Karangahape Rd, the stretch of inner-city Auckland which has long been the unofficial home for the city’s queer culture, it could be part of a network of institutions such as Rainbow Youth and Eagle Bar and would enjoy more foot traffic. But the rent in the inner city is high — a bit too high. Instead, Aotearoa’s lesbian history is neighbour to old cars and tyres.

A bell chimes as you enter. Past the little table of flyers promoting queer social services and events are the two items which started it all: a quilt made from 48 graphic t-shirts, each with a lesbian story, and a collection of badges arranged to form a vulvic shape on black velvet. In 2003, the advocate, researcher and artist Miriam Saphira tried to donate these pieces to the Lesbian and Gay Archives of New Zealand in Wellington, but was turned down because the archive staff said they couldn’t properly care for textiles, metal or plastic. Objects of lesbian cultural history tend to be absent in major museums, and there’s a general worry that lesbian-specific parts of queer history in particular have not been the focus of preservation or historic cataloguing. It occurred to Saphira that a dedicated lesbian museum would fix that problem.

Saphira and the other women who helped establish the museum in the mid-2000s wanted it to celebrate ordinary lesbians, and were particularly keen on using an “old-fashioned girls’ name”. Many options were raised: Agnes, Agatha, Elizabeth, Maud, Hermione, Elsie, Charlotte. There they paused. Two Charlottes in the local lesbian community had recently died. Both had been members of the Kamp Girls Club, the first openly lesbian social club in Auckland, which had a reputation for boisterous parties in the 1970s. Charlotte Smith had organised events there, and Charlotte Prime had been on the committee. The Charlotte Museum Trust was registered in May 2007.

In the 1970s lesbian feminist warriors adopted labrys, ancient Greek double-headed axes, as a symbol. Labrys have a long symbolic history, originally belonging to female goddesses in the Minoan religion in Crete (circa 2700–1450 BCE). Today they are envisioned to cut through webs of patriarchy.

Buxton was at home in Auckland, pregnant with her first child, when she saw a little ad in the Tāmaki Makaurau Lesbian Newsletter (which was printed and delivered to subscribers monthly from 1990 until 2015) asking for volunteers to help with cataloguing for a new lesbian museum. She had time and a history degree, and the idea appealed to her greatly. She ended up at Saphira’s house, cataloguing her artworks, artefacts and books, which became the foundation of the museum’s collection. “I had a delightful time,” Buxton says, “listening to her stories.”

Of Saphira’s many objects, 338 were badges collected over the 1970s and 80s. A badge might seem like an easy item to catalogue and store — small, sturdy, and durable, made from metal and protective plastic casings. But the opposite turned out the be the case. “Once they get to a certain age, they become quite delicate,” says Buxton. The metal a badge is made from is susceptible to rust — to help prevent this, the badge board is carefully encased in UV filtering Perspex.

Each badge bears a slogan for the fight for lesbian rights, and adjacent political activity like movements against violence and apartheid, and for environmentalism and feminism. I admired them with the visitor host, Max Glass, who helpfully pointed out slogans like “Macho Slut”, “Warm Fuzzy Dyke” and “We Don’t Need Balls to Play”. “Everyone who sees the badge board, they all just love it,” says Buxton. Each represents a small push towards liberation, a coin-sized act of rebellion. Still more are stored in jars upstairs.

Also on display is a pair of mauve socks from the 80s printed with a purple double-Venus (those familiar two interlocking “female” symbols which represent a lesbian couple or sapphic love in general), a toothbrush in the shape of a Barbie leg, and a jar of apple-flavoured Lezzo-brand tea. The latter, an import from Turkey, was a staple in lesbian households of the 1970s and 80s — though memories of its presence aren’t accompanied by memories of anyone actually drinking it.

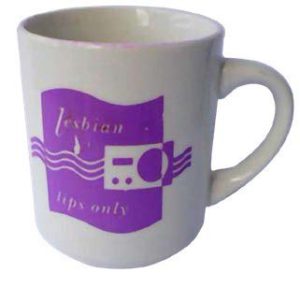

Much of what’s on display is homeware: objects which were once a part of people’s everyday lives — ordinary items that are mostly less than 50 years old. “This everyday personal stuff is the crux of our collection,” says Buxton. It paints a picture of the domestic spaces lesbians have made for themselves, departures from heteronormative ideas of home, such as the coffee mug that says “Lesbian lips only” in a mauve 1990s-style graphic.

Sometimes donors aren’t sure that their items are “special” enough, but at the Charlotte Museum they collect anything related to lesbian culture and identity out of a genuine concern that if they don’t, the history will be lost altogether. “We can’t restrict ourselves, because then we miss vital pieces,” says Buxton. “There’s not a lot of collecting going on elsewhere.”

The Charlotte Museum also saves items from other institutions. Inside the work room, a mountain of boxes are filled with books waiting to be catalogued. It’s the first pick of the remnants of the recently closed Women’s Centre Library in Grey Lynn, Auckland. On the museum library shelves, book spines marked with fluoro-pink stickers indicate volumes once held by a now-closed women’s studies department library at the University of Waikato.

The publications here are rare. They’re from small print runs, are out of print and specialist. There are very few rainbow museums, libraries or archives in the world, and they tend to be small. For people looking into queer history, it can be hard to find information. As a result, the Charlotte is often contacted by researchers. Recently, one PhD student from the University of Auckland has been looking into the history of non-binary identity in Aotearoa, and another at the history of same-sex couples having children. “It’s fun and exciting to be able to help,” says Buxton. Usually, the museum can find and share a few relevant books.

The Charlotte Museum is growing and evolving. New items are being donated weekly, the library is expanding, contemporary art is displayed in the galleries, and people are re-cataloguing, digitising and guiding. There’s a lot of activity, but when Covid hit, the museum lost much of its volunteer base. It was largely run by a small group of queer people in their 60s and 70s, who are vulnerable to the virus. By securing more funding, Buxton was able to hire staff and grow the museum’s operational capacity, especially on digital platforms. An internship programme with students from the Museums and Cultural Heritage course at Auckland University has fresh faces caring for the collection and writing for the website.

“I don’t think we’ve really recovered yet, but we’re heading upwards,” says Buxton, “Covid taught us all some lessons. And now it’s all about rejuvenation and resetting how we do things. It’ll be interesting to see.” Outside, the rainbow flag lifts in the breeze.

Charlotte Museum is open Wednesdays, Fridays and Sundays or by appointment, 8a Bentinck St, New Lynn, Auckland. charlottemuseum.co.nz

In the 1990s, mugs were made for the Lesbian Community Radio. From 1984 it broadcast lesbian voices which were under-represented on mainstream media. It has since broadened its scope and become QUILTED BANANAS Radio.

Gabi Lardies is North & South’s junior writer, a role made possible by NZ On Air’s Public Interest Journalism Fund.

This story appeared in the March 2023 issue of North & South.