Culture Etc.

Ōtepoti crime writer Vanda Symon is also current president of the New Zealand Society of Authors Te Puni Kaituhi o Aotearoa.

Returning to the Scene of the Crime

After a decade away, New Zealand’s modern-day “Queen of Crime” is back.

By Thomas McLean

In 2012, Vanda Symon was on a roll. The Dunedin-based writer had published five novels in six years and established herself as one of New Zealand’s leading authors of crime fiction. Her first four novels featured Samantha Shephard (a police constable from Mataura who moves to Dunedin to become a detective) solving crimes, dealing with male colleagues who underestimate her, and all the while giving readers a taste of life in Otago — a taste that usually included Milo and a packet of Toffee Pops. In a genre still mostly populated by strong, moody, male investigators, and usually based in big-city Britain or the USA, it was refreshing to read about a detective-in-training with a nagging mother, sharing a flat with her best friend in New Zealand’s favourite university town.

Symon’s fifth novel, The Faceless, was a standalone thriller set in Auckland which pushed her fiction in new directions, encouraging readers to think about contemporary social issues, like homelessness in Aotearoa’s biggest city or the influence of Christianity on our Pacific communities. Like its two predecessors, The Faceless was nominated for a Ngaio Marsh Award for Best New Zealand Crime Novel. Symon seemed on the cusp of bigger things.

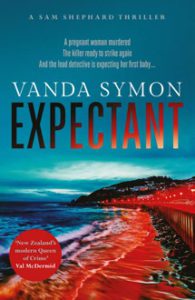

Then, for more than a decade, silence. Admirers of Symon’s fiction (she has often been dubbed New Zealand’s “Queen of Crime”) will be thrilled to learn that Detective Sam Shephard will return to action early this year with the release of Symon’s sixth novel, Expectant. The title points to both an unsolved crime (the murder of a pregnant woman) and Sam’s state (she too is expecting a child). But it might also be a sly nod to the many readers who have been waiting eagerly for Sam’s return. “It’s been a long gestation!” jokes Symon, whose writing was derailed for some years by deciding to undertake her PhD. While only a few weeks have passed in Sam’s universe, a lot has happened in ours between 2012 and 2023. Detective Shephard returns to a more complicated world, and a much livelier literary scene — both in Dunedin and in New Zealand.

One could argue that crime writing has an ancient history going back (at least) to Genesis. A lot of dark narratives have borrowed from the serpent’s evil persuasion, Adam and Eve’s blame game, and Cain’s sudden brutality. Any number of Shakespeare’s tragedies, including Hamlet and Macbeth, hinge on murder, guilt and restitution. A more recognisable form took shape in the 19th century, first in Gothic fiction (the kind of novel Jane Austen mocked in Northanger Abbey), where seemingly supernatural occurrences in ancient castles are often explained by bad human behaviour; and later in Sensation fiction of the 1860s (think Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White and Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s Lady Audley’s Secret), works that would be reflected in a later New Zealand classic, Eleanor Catton’s The Luminaries.

While the whodunnit element was well established in popular fiction, another key component was still missing: whosolvedit? Literary scholars will no doubt debate this one for decades to come, but Auguste Dupin, the gentleman sleuth in three of Edgar Allan Poe’s stories from the 1840s (most famously “Murders in the Rue Morgue”), is a favourite starting point, closely followed by the all-seeing Inspector Bucket in Charles Dickens’ Bleak House. The form really came into its own at the end of the 19th century, with the appearance of Sherlock Holmes. Between 1887 and 1927, Arthur Conan Doyle produced four novels and 56 short stories featuring the violin-playing polymath, most of them narrated by Holmes’ sidekick and sounding board, Dr John Watson.

The form continued to develop in the 20th century, responding to two world wars, and taking in the “Golden Age” of detective fiction, which produced the four Queens of Crime: Agatha Christie, Margery Allingham, Dorothy L Sayers, and New Zealand’s own Ngaio Marsh. While Christie’s Belgian protagonist Hercule Poirot probably remains the genre’s most famous investigator, the works of Marsh hold a special place in Aotearoa, both because of the author’s deep connections to her birthplace, Christchurch, and because she occasionally sent her London detective Roderick Alleyn to unravel crimes in New Zealand.

A grittier, more complex approach to fictional crime fighting developed after the World War II, through the work of writers like Evan Hunter. This new branch of crime fiction, the “police procedural”, offered a more realistic portrayal of police work, from bureaucratic battles to forensic science. And the old centres of wrongdoing — Los Angeles, Paris, New York, London — were joined by any number of settings, not least newer favourites Scotland and Scandinavia. Indeed, place became almost as important as character and narrative as the genre evolved. Along with Holmes’ London and Maigret’s Paris, readers have enjoyed discovering John Rebus’ Edinburgh, Armand Gamache’s Montreal, and closer to home, Sam Shephard’s Dunedin.

Sam Shephard was not supposed to disappear for 11 years. Symon was already sketching out Expectant in 2011, while finishing the series’ fourth novel, Bound. But a University of Otago summer school paper on forensic biology with the late Jules Kieser — an opportunity to extend her knowledge in ways that might enrich her fiction — led Symon to a different kind of writing. “After the course he said I should consider doing some postgraduate work,” she tells me. “I decided to do a PhD. It seemed like a good idea at the time.” Symon says this with a twinkle in her eye; but she saw it through. Working in the Science Communication programme at the University of Otago, Symon completed a study of the ways scientific knowledge is transmitted in crime fiction. She focused on Ngaio Marsh (“I just wanted to do something that acknowledged her amazing work”), but Symon also called on her global network of fellow crime writers to answer questions about the role of science in their works.

Symon admits that she struggled with the academic approach to writing, where discoveries are all laid out in the opening pages. “My supervisors would not let me add a surprise ending to my PhD thesis, which was really, really annoying.” But her doctoral research was a canny way to stay within the world of crime fiction while also extending her own skills. Her time in academia led to a position as research fellow at Otago’s Va‘a o Tautai — Centre for Pacific Health and, more recently, to an appointment as associate dean Pacific for the university’s School of Pharmacy (Symon trained and worked as a pharmacist before taking up writing).

Meanwhile, interest from the other side of the globe kept Symon in the professional crime writing game. Craig Sisterson, an expert on crime fiction and founder of the Ngaio Marsh Awards, lent British indie publisher Karen Sullivan a copy of Symon’s first novel Overkill. On the train ride home, Sullivan was so caught up in the story that she missed her stop. Symon was soon signed to Orenda Books. As part of the agreement, Symon revised each novel for a European readership: not by removing local references, but rather by explaining them and, when appropriate, adding still more. “Karen loves books that have a sense of place,” Vanda explains. “She wanted them to be more Kiwi.”

While many writers hate revisiting old work, Symon found it reassuring. “It was lovely to read them and not cringe.” The revisions also helped with the new work; as Symon puts it, “it was lovely to get Sam in my head again”. Symon’s first two novels appeared in the United Kingdom in 2019, with her subsequent works released at yearly intervals. The Faceless, renamed Faceless, was published in August 2022; so, for Symon’s northern hemisphere readers, Expectant will appear after a wait of months rather than years.

Crime author royalty: Ngaio Marsh, Agatha Christie, Dorothy L Sayers and Margery Allingham.

There is a particular pleasure to good crime fiction. At its core, the genre usually concerns a single character with problems to solve: some of them criminal, some personal. The pages flash by — there’s a physical satisfaction in feeling the weight of the book quickly transfer from the right to the left hand — and one rarely needs to go back to separate the good guys from the bad guys. For many readers, it’s a contest: can I identify the killer before the detective does? There’s also the vicarious thrill of entering the mind of both criminal and detective.

Symon’s novels often pull the reader in with a visceral, opening scene of violence. She’s also very good at the big set piece: a runaway circus elephant raising havoc on Dunedin’s Andersons Bay Rd; a grounded container ship in Aramoana that turns law-abiding locals into callous thieves. Despite the sometimes salty language of her characters, on the cosy-to-grisly meter, her Sam Shephard novels are definitely on the cosy side. We may read primarily to solve a murder, but we’re also interested in Sam’s friendships and relationships.

Genres that do not change with the times tend to fade away. During our discussion, Symon reflected on the many technological and societal changes that have altered crime fiction. It is much more difficult for a character to disappear today than it was in Sherlock Holmes’ London. If they can’t be tracked using their mobile phone, they will probably be picked up by CCTV. And how should one tell a story in the Covid era? Five years ago, a masked man in a beanie would have been an obvious villain; these days, he’s probably just picking up almond milk. Symon wonders if our rapidly changing society explains the recent taste for crime fiction set in the past.

Characters, too, need to change. Over four novels, Sam has gone from an inexperienced police constable in Mataura to a formidable detective in Dunedin. In this latest book, she seems on the cusp of that most terrifying assignment of all: parenthood.

And then there’s Dunedin. Val McDermid, one of the genre’s current royalty, has written that crime fiction is “a genre that appears to have been designed specifically for our dark winter skies and the dour Presbyterian side of our national character”. McDermid is referring to Scotland, of course, but the same could be said of the Edinburgh of the South. From its moody music to its Gothic Revival architecture, Dunedin has all the ingredients a crime writer could want. “There’s an elemental thing for me with Dunedin,” says Symon. “The hills, the sea, the green belt, the Victorian alleyways, it all added up to this place that had excitement but also a slight menace to it.”

In the last decade, Dunedin has become a centre for crime fiction. The University of Otago’s Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies (CISS) is co-run by Liam McIlvanney, a scholar of Robert Burns and author of four crime novels, most recently The Heretic. McIlvanney, whose father, novelist William McIlvanney, is often cited as the father of Tartan Noir, has brought a kaleidoscope of crime writers to Dunedin, including Ian Rankin, Liz Nugent, and Adrian McKinty. The centre hosts an annual visit from Val McDermid, who meets with postgraduates and lectures to undergraduate students on the history of the genre.

While CISS may have added further Celtic flavour to Dunedin’s already very Scottish heritage, its criminal turn reflects a broader shift in New Zealand writing. Symon credits the introduction of the Ngaio Marsh Awards in 2010 with putting crime writing in the spotlight. In the past decade, the number of nominated works has leapt from perhaps a dozen to more than 60. Symon has herself been a judge for the award for first novel, so she has seen at first hand the growth in interest and quality in recent years, noting the success of younger writers like JP Pomare and Jacqueline Bublitz. Meanwhile, another strand of crime fiction, evident in Michael Bennett’s Better the Blood (2022), calls attention to New Zealand’s troubled history. Far from being an offshoot of northern hemisphere crime writing, New Zealand crime fiction is quickly developing its own unique identity.

No matter the degree of success it achieves in the wider world, Symon is confident that the Aotearoa writing community will remain a warm and supportive place. “We’re all each other’s best cheerleaders,” she assures me. But she’s tight-lipped about Detective Shephard. Will she catch the killer? Will she embrace parenting? And will she keep eating all those Toffee Pops? We’ll all just have to keep reading.

Dunedin’s St Clair Esplanade is a key setting in Vanda Symon’s new novel Expectant. Photo: Thomas McLean.

Expectant by Vanda Symon (Orenda Books) will be available from 16 February.

Thomas McLean teaches English at the University of Otago.

This story appeared in the March 2023 issue of North & South.