Culture Etc.

The artist with her PhD exhibition, Soft Feelings, at AUT’s St Paul St Gallery. Photos: Emily Parr and Laree Payne Gallery

Still not knowable

The unpredictability and challenges of working with clay are what drew artist Emelia French to change her focus from painting to ceramics. The Taranaki-born artist and researcher now lives in Auckland and has just completed a PhD at Auckland University of Technology.

By Theo Macdonald

What types of clay do you like to work with?

I work with Aotearoa-made clays and a few that are Australian-sourced. I’ve been using bought clay and the clay manufactured at Driving Creek Pottery (established by the late Barry Brickell in the Coromandel). I’m interested in clay’s relationship to the earth, and thinking about that as a poetic metaphor, but also literally, through the material, so I’ve become more local-based. We have great terracotta clays in New Zealand.

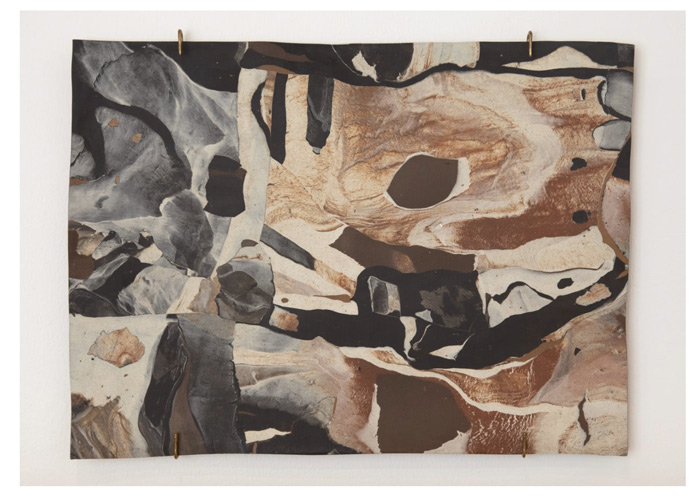

Wall tiles by Emelia French

How does the clay you use inform your making?

I’m mixing 11 different clay bodies together, and my works are fired at 1200°C over 40 hours, so there has to be a level of compatibility right through the firing stages. I think of the different clays as all having separate personalities, so I’m working toward a kind of friendship between them. If I add a new clay body it can throw the whole formula out, so it’s important to have a feel for which ones can withstand different uses. My making is quite impulsive and intuitive, but I’ve accumulated a lot of material knowledge over the past three years. I don’t have any of it written down, but I know what works and what doesn’t, so when I go to make new work, I’m aware of where I’m asking a clay to go beyond its comfort zone and how much I can push it.

Do you enter the studio each day with a strong idea of what you’re going to make?

The way I work with clay is iterative, so a mark in one work feeds the next, pulling that mark out or exploring it further. You can tell the works belong with each other through a shared tone, a series of gestures, or a colour palette, because they’re all getting fired through the same firing group and tend to have the same variations. There’s not really anything else I can predetermine beyond that. The foreground and background are never settled until it’s been fired because some colours pull forward, and others disappear, or get consumed by other clays in the firing process. In my PhD, I ended up describing my methodology as a soft approach; basically, this means trying to work in a way that’s open to contingency, being receptive to what the material needs to do, or wants to do. Clay has so much pushback when I work with it, in terms of mass and weight, and how much it changes between being raw and its fired state.

A work from Emelie French’s PhD exhibition, Soft Feelings.

How do you describe your work compared to that of other contemporary, local ceramic artists?

I was on a panel at Objectspace [art gallery in Auckland] last year, where Becky Richards, Sung Hwan Bobby Park and I were asked to define ourselves in relation to terms like artist, potter and ceramicist. None of us really had a conclusive outcome, but we all identified that we’re part of a generation of people trained through art school, under sculpture and painting disciplines, with clay as our material. That leads to quite a different approach from studio ceramics, but within all of us there is a reverence for that tradition as its own discipline. Ceramicists get my work with a different appreciation than a general audience. Ceramicists are often pretty diehard around their love and obsession with the material and figuring it out technically and chemically. With my tile series, there’s an appreciation from an outsider’s perspective for the visuals, for the atmosphere of them and the foregrounding of clay’s materiality, but when ceramicists come in to see my work, we will have a different kind of conversation. They’ll look at how thin they are, how these clays hold together, and ask about what firing process I’ve used.

Where do you anticipate your work going next?

One way I’m starting to branch out is by looking to incorporate other materials. Today, I’ve been experimenting with pouring molten bronze into clay. I’ve made these works that have hollow pieces. The clay gets heated up to 1000°C, so it’s at a compatible temperature to receive the molten bronze, and then we’ve been pouring the bronze into these cavities and putting it back in the kiln to cool down. Different things are emerging conceptually for me; the most important thing is that the work sustains that feeling of hesitating on clarity of meaning, so they keep the poetry about them. That’s kind of my guiding principle. I started working with clay three years ago, and there’s a naivety around those first works that I have to be careful not to lose as my competence in the material grows. It’s about feeling out that boundary space between what is known and still not knowable. Folding in new clay bodies or going larger in scale are some ways I maintain that threshold.

See Emelia French’s work at lareepaynegallery.com.

Theo Macdonald is North & South’s junior staff writer, a role supported by NZ on Air’s Public Interest Journalism Fund.

This story appeared in the August 2023 issue of North & South.