Robot Heart

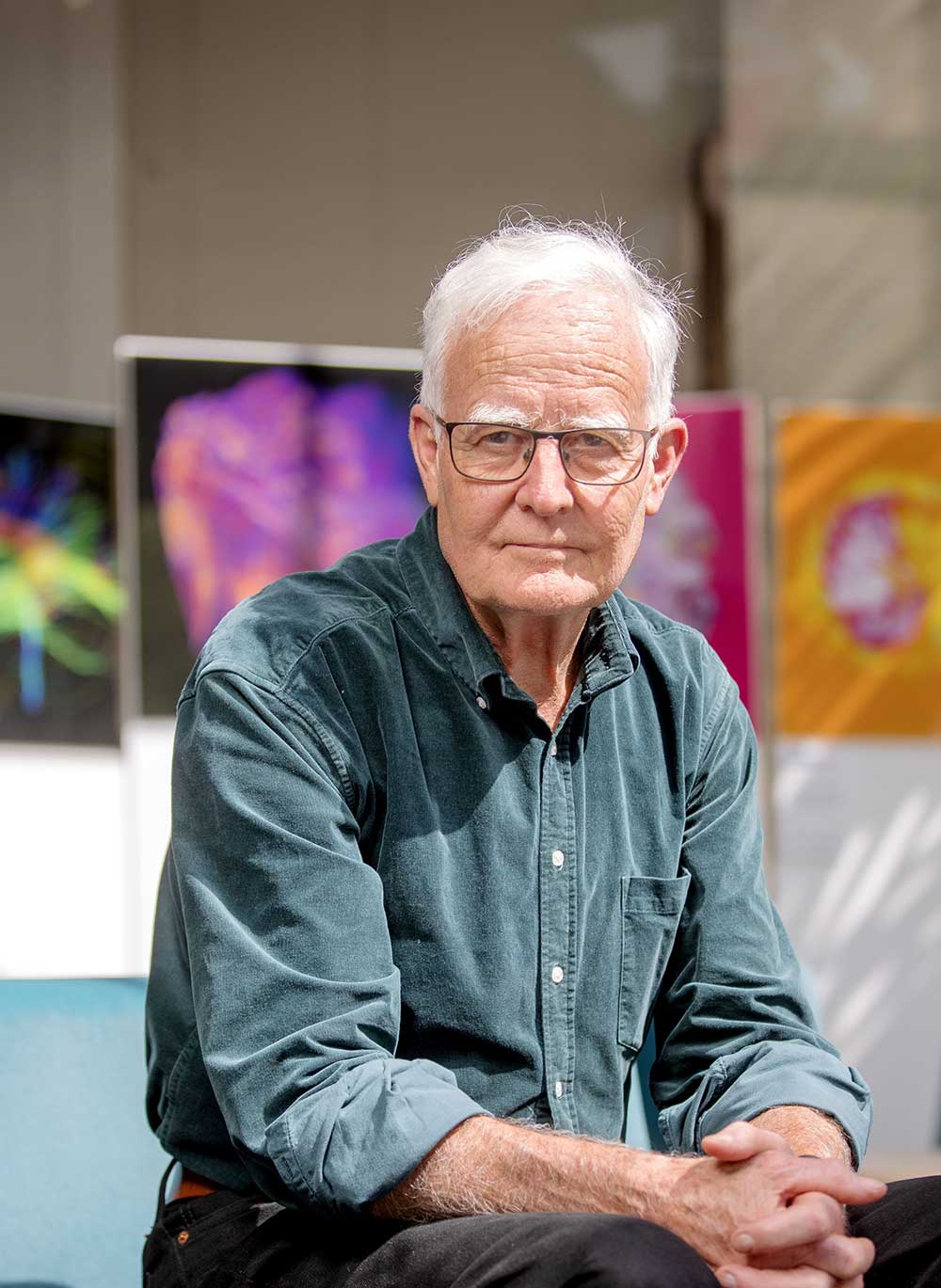

World-renowned New Zealand scientist Peter Hunter is well on the way to transforming healthcare through digital modelling of the human body. Just don’t expect him to get over-excited about it.

By Nikki Mandow

Additional Reporting: Megan Fowlie

If you want to find out about the career of Distinguished Professor Peter Hunter, arguably one of New Zealand’s leading scientists on the global stage but hardly a household name at home, you could do worse than start with an old copy-paper box on the floor of an office on the sixth floor of the University of Auckland’s warren-like Auckland Bioengineering Institute (ABI).

Inside the box is a mad jumble of magazine articles and newspaper clippings — many upside down, all out of order. Some of the globe’s most influential publications have featured stories about New Zealand’s “mild-mannered academic”: The Economist, Time, The New York Times, New Scientist, in addition to the stories from practically every local media outlet, past and present.

“Cyberheart,” proclaims New Scientist in a cover story in 1999. “It beats, it throbs, and it will change the face of medicine.”

“Virtual stunt doubles for your organs,” says Wired in 2005 — the same year Hunter was named New Zealand’s smartest scientist by Metro. “The doctor will see your prototype now.”

“Why some scientists believe the future of medicine lies in creating digital twins,” is the headline in a Time article from April this year. The several hundred clippings form a snapshot of a vision — variously described by colleagues and journalists as everything from “on the edge of crazy” to “stupefying” — of an engineer who started work around 40 years ago combining biological experimentation (thousands of minute measurements done on hundreds of paper-thin slivers of heart tissue) to produce millions of data points for digital models.

His goal? By using the laws of physics, mathematical equations and computer power, the engineer, together with physiologist colleague Professor Bruce Smaill, wanted to make an interactive model of the human heart to understand illnesses better and test therapies.

Peter Hunter’s virtual heart has come a long way in two decades, but it’s still not finished. Teams of scientists around the world, including many at the Auckland Bioengineering Institute, continue to refine and enhance the digital heart.

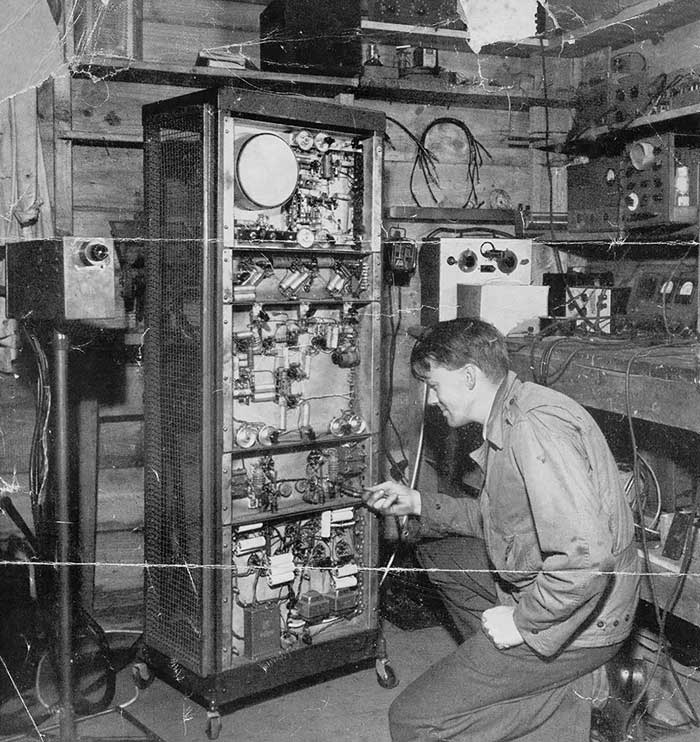

Father Les, an inventor and engineer.

Peter and brother Ian Hunter.

In the meantime, Hunter’s vision has grown. He and his colleagues in New Zealand and overseas are creating digital models of the lungs, the gut, the musculoskeletal system, the brain, the uterus. The institute’s signature programme is called 12 Labours — named for the dozen mythical and supposed insurmountable challenges given to Greek hero Hercules to enable him to atone for killing his wife and children. The ABI’s feat of ingenuity and excellence is to understand and map our 12 organ systems. The $15-million project’s ambition is to develop personalised digital models of a whole body — a real, virtual human.

Solve the mathematical modelling, apply computational power and it would be possible to create a digital twin of every patient.

Instead of researchers testing the impact of a treatment or drug on random people in trials, and then doctors hoping that same drug or treatment will work in a similar way with the individual in front of them, Hunter’s vision is that doctors will be able to test the impact of a medical intervention on anyone, using their digital twin.

We live in the age of data. Anyone with a smartphone can navigate the world, translate languages and ask ChatGPT for help to pass a law exam. But in 1997, a time before the global tech giants and ubiquitous handheld computers called smartphones, a group of international scientists, led by Hunter, met in St Petersburg in Russia and set up the Physiome Project.

The project’s goal was to develop computational models of cells, tissues and organs to improve understanding of human health and disease. The scientists would do that by investigating how every component in the body, from molecules up to organ systems, worked as part of the integrated whole.

“That was probably the moment when I really dedicated my career to looking at integrative physiology in a much more holistic sense,” Hunter says.

Was that vision even possible in 1997?

“No,” he says. “It was a ridiculous, ridiculous dream. I mean, we were incredibly naive; I probably still am. But in terms of complexity, I’ve never doubted that, in the end, it would be possible because biology obeys all the laws of physics.”

The opposite is true as well. Physics and mathematics can explain biology. Timaru-born physiologist and Oxford academic Professor David Paterson was involved with the Physiome Project from its early days. He says it was perceived as on the edge of crazy “and still is” — like the Genome Project, but orders of magnitude more challenging.

“Often in science we take Kodak moments,” he says. “We take a picture of how truth is at that moment, in that spatial domain. What Peter is trying to do is to make a movie.

“The framework is complicated,” Paterson says. “It is due to space and time. And the space from the very reductive to the integrative, from the protein to the human, from the nano-scale to the metre- scale. Then, over time, from early development to when we die.”

The first toddler on television

It’s 1950 and a toddler pushes his little bike across a crackly fluorescent screen. The three- year-old is the star of New Zealand’s first-ever television broadcast; his father Les, an electrical engineer and inventor, has been commissioned by the national broadcasting service to build an experimental closed-circuit TV station in his backyard.

Ten years before television comes to New Zealand, Les films his wife and son, using a camera he has built himself. The little boy will become Distinguished Professor Peter Hunter, future founder and the first director of the Auckland Bioengineering Institute.

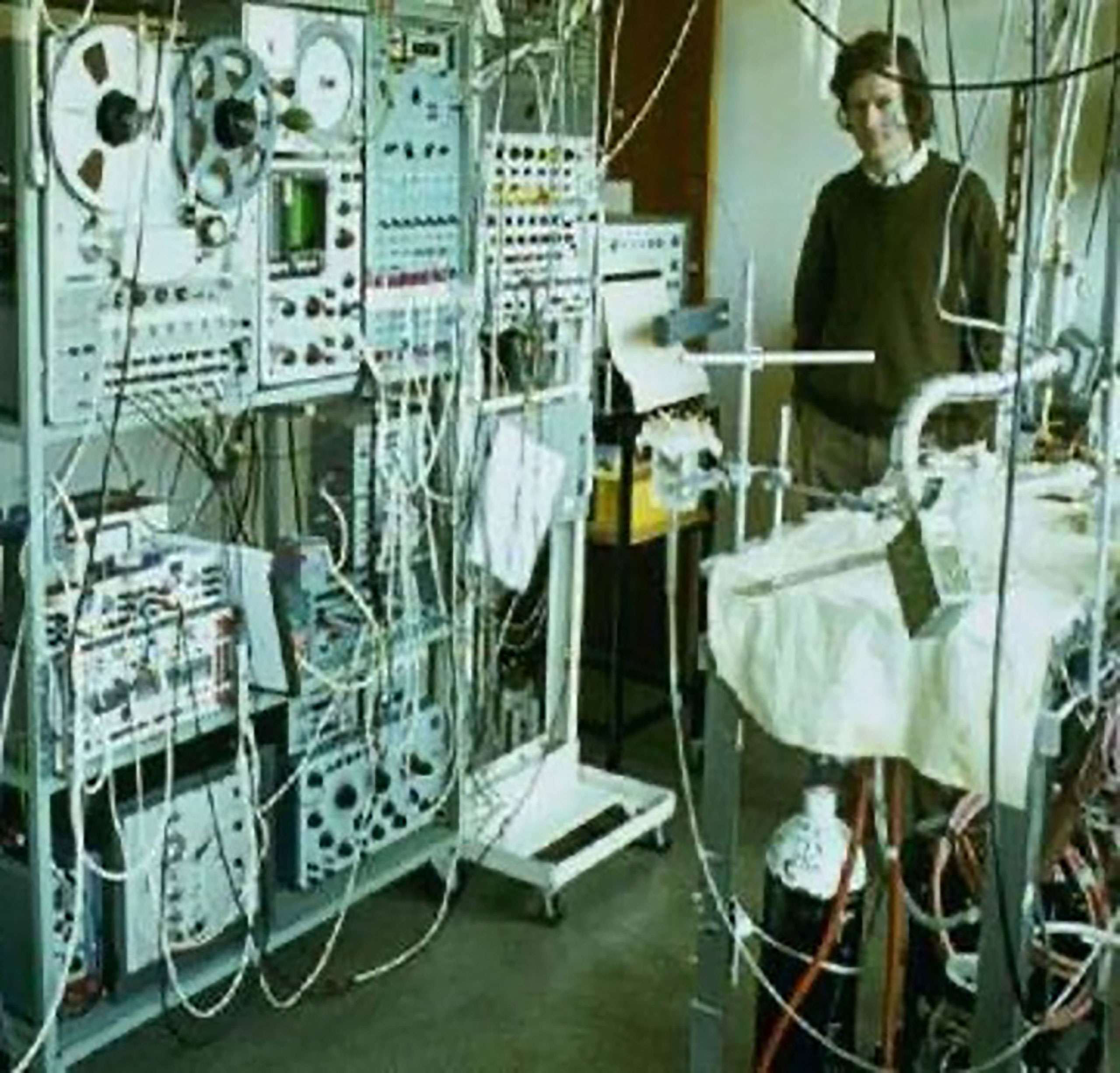

Peter Hunter in the laboratory at Oxford University.

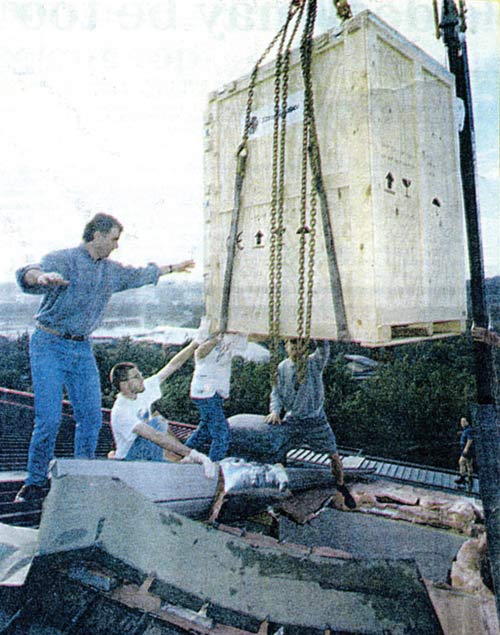

Bringing in the MicroVAX by crane.

A newspaper story from the 1950s says of Les Hunter: “Versatile… that’s Les Hunter. At various times he has been equally at home at the controls of a flying boat, troubleshooting in a laboratory, installing substation cable, exploring geothermal power options in the Philippines and El Salvador, or making a closed-circuit television system.”

Free-range parenting

Les Hunter builds workshops in their bedrooms for Peter and his younger brother Ian, once they are (more or less) old enough to use adult tools. Five or maybe six years old. When the boys express an interest in a particular field, equipment — but no explanations — appears mysteriously on their workbenches.

The pair plunge into electronics with gusto but minimal supervision. Peter Hunter repairs valve radios for the neighbours; he spends the pocket money on upgraded tools — high-spec drills and vices. When Ian Hunter gets into chemistry, their father extends his bedroom to incorporate a lab, complete with fume hood and chemicals. Ian Hunter goes on to make explosives big enough to blow “small craters” in the ground at One Tree Hill.

Les Hunter, busy with his business and his own projects, is hands-off. Still, Peter and Ian, who will each become world-leading scientists, wonder in retrospect if their father’s tactics, were a strange form of brilliant parenting.

Big data, bigger computers

In the mid-1980s, Peter Hunter, then a tall, skinny bioengineering researcher, returns from a sabbatical at McGill University in Montreal and announces his team needs significantly more computing power. He and colleagues persuade the powers that be to buy a MicroVAX, a machine which, at that time, cost the equivalent of a couple of years of an average salary.

Later, the building managers discover they need to hire a crane and take off part of the roof of the Engineering School to bring in the machine. Astonishingly, they agree.

A decade or so later, Hunter will convince the University of Auckland to upgrade; this time to a Silicon Graphics computer, a machine with state-of- the-art 3D visualisation capabilities worth more than $2 million.

It’s a vast sum in 1995, when the median house price is less than $150,000. But for a time the University has one of the most powerful computers in the southern hemisphere.

In 1997, Hunter returned from Oxford, as had his longtime colleague Smaill from Imperial College in London.

They and a small number of students bounced between the Department of Physiology and the Department of Engineering Science trying to do work which combined but did not fit either discipline.

“It was hopeless. No one wanted to give us space,” Hunter says. “At that time Engineering Science did maths, but it didn’t do experimental work — everyone was very protective of their space.”

The Engineering Science department had the equipment the nascent bioengineers needed for their calculations and equations, but lacked space to conduct experiments. Hunter and his team had collected slivers of heart tissue to obtain the data they needed. They needed more than a computer and a desk.

Peter at work with the 12 Labours project team.

When John Hood (later Sir John) became Vice-Chancellor of the University of Auckland, he understood what Hunter and colleagues were doing and suggested they move to 70 Symonds St at the University of Auckland’s city campus. There was space on one of the floors. Hunter remembers walking down Symonds St with the then-head of UniServices, Dr John Kernohan. “And he said to me: ‘One day, you will occupy the whole of that building.’ And I looked at him as if he was absolutely mad because we had one floor. But he was right.”

Hood, who went on to become Vice-Chancellor of Oxford University, remembers Hunter as a scholar with vision, “But someone who didn’t sing it from the rooftops”. Hunter has another claim to fame, Sir John says — bringing decent coffee to the University. The first thing he did when he moved into the director’s corner office was buy a top-of- the-range coffee machine. As the ABI took over new floors, so other state-of-the-art coffee machines appeared.

To call Hunter “understated” is to understate understatement. He talks quietly, calmly, focusing on his team’s rather than his own achievements. He explains science simply, without being condescending or becoming excited.

It’s one of his hallmarks, says ABI senior research fellow Mark Trew. “If you had a group of those really top men and women scientists — the ones that operate at Peter’s level — he would arguably be the least charismatic and energetic of those.”

But arguably the most effective. Somehow the lanky scientist from the bottom of the world has managed to persuade some of the field’s top international researchers and talent to come to New Zealand. Students and postdocs working at the ABI now come from more than 35 countries; with many going on to work with the ABI’s commercial spin-off companies.

“I often get the sense with some of the more charismatic international scientists that they operate at quite a high marketing level,” Trew says. Instead, Hunter exudes an important level of trust. Ian Hunter says his brother is “modest and self- effacing, not someone who comes across as a huckster”.

Those character traits can hide his achievements. “The ABI is the best in the world,” Ian Hunter says. “New Zealand with its population of five million; how can you have the world’s most advanced bioengineering institute and it’s in Auckland?

“It’s crazy, and it’s all because of Peter’s ability to calmly, rationally explain to people why it’s important for New Zealand to have something like the ABI, and his ability to attract first-rate people and inspire them to do their best.”

As Smaill says: “Almost no one leaves.”

In 2021, the ABI calculated that 34 percent, or 102 of its academic and professional staff were alumni. Mark Trew is one of the staffers who started working with Hunter in the 1990s and 2000s — and is still at the ABI.

“If you were to talk about all of us who had been with him over the years, we would feel a lot of confidence following him to wherever, because you don’t get the feeling that he’s just trying to sell you on a vision with no substance.

“He’s clearly thought it through, even though there are parts of that vision where, even at this stage, it’s still unclear if they’re ever going to be quite achievable. You know, one individual, even over the span of his whole career, is not going to be able to solve all these problems.”

A further trademark, say colleagues, is the ability to bring the world’s top scientists in the field together. Marco Viceconti, Professor of Computational Biomechanics at the University of Bologna in Italy, first met Hunter at a conference in Calgary in 2002, where his address about the Physiome Project led to the use of the ABI’s organ- specific models as clinical decision-making tools.

Viceconti won funding from the European Commission for a project he called “STEP: Seeding the EuroPhysiome” and approached Hunter to chair the international scientific advisory committee.

“He could have easily reacted in an adversarial way. At that point, he had been preaching the Physiome vision for more than 10 years. The ABI was light years ahead of anyone else in building digital humans, and Peter was the recognised leader of this emerging field we now call in-silico medicine.

“On the contrary, he enthusiastically accepted my invitation, opened his portfolio of international contacts to me, and tutored me in the delicate art of scientific consensus. Peter is full of qualities, but the one I like most is his ability to bring people together and guide them to achieve things that alone would have been inconceivable. The ABI is the perfect example of this quality.”

When, in 2011, Viceconti was offered the chance to build his own research institute looking at in silico medicine, he used the Auckland Bioengineering Institute as the blueprint.

“In silico medicine (also known as computational medicine), is becoming mainstream, mostly because of Peter’s leadership,” he says. “But the ABI is still the role model we all refer to.” When he tells the story of the birth of the Insigneo Institute for In Silico Medicine at Sheffield University in the UK, he uses a slide entitled ‘Dreaming of ABI’.

There are now multiple digital-twin projects in the world. But the ABI can rightly claim to continue to be the frontrunner, the only one based on physics not simply on AI models. It’s not that the others aren’t going to deliver useful outcomes, Hunter says. But nothing like what the ABI will produce.

Is he saying the best digital twin model could come from New Zealand?

“Absolutely. I’m sure it will.”

And when it does, it will be open-source. Though he adds an important caveat.

“That doesn’t stop us taking commercial advantage of it, because we have the inside running on how to do it. And we’ve got to continue to start companies that can build on that, because that’s the only way you’re going to get it into widespread use. So, there’s nothing incompatible between an open-source, open-science approach and, in parallel, developing the ability to create spin-out companies which exploit that knowledge that we’ve gained.”

”There’s nothing incompatible between an open-source, open-science approach and, in parallel, developing the ability to create spin-out companies which exploit that knowledge that we’ve gained”

The ABI has a whole floor called Cloud 9 dedicated to start-ups — a launchpad for them to find their feet and external investors. More than 20 spin-off companies have been created, including gut diagnostic device company Alimetry, AI-empowered joint replacement software firm Formus Labs and pelvic floor training device maker JunoFem. Perhaps best known is Mark Sagar’s Soul Machines, which now employs more than 200 people and has a second research lab in Phoenix, Arizona.

It makes sense then that Hunter leads the fledgling Medtech-iQ Aotearoa (iQ stands for innovation quarter).

This ambitious project aims to create a nationwide ecosystem that links researchers, the healthcare system, communities, start-ups, investors and international opportunities around the medical technology space.

One goal is to foster medtech companies in New Zealand, to grow future companies like Fisher & Paykel Healthcare. The wider opportunity is for Medtech-iQ Aotearoa to bring biotechnology research and clinical practice closer together to improve outcomes for patients through better data use, interpretation, diagnostics, therapeutics and medical devices.

“The notion of Medtech-iQ Aotearoa as a kind of integration of bioengineering with medicine is critically important, says Smaill, Hunter’s longest- serving research collaborator. “The more clinical researchers are involved, the better it is for bioengineering, because the problems we deal with then become the right problems, and that also provides a framework in which to develop commercialisation.”

Peter Hunter is now 75. In 2023 he stepped down as director of the Auckland Bioengineering Institute, although he’s not leaving the lab anytime soon.

Is he disappointed that his vision, created all those decades ago, hasn’t come to fruition? Does he worry it might never happen? It has been one of the frustrations, he says, that funding bodies tended to be prepared to give grants for specific projects around certain organs — the heart, the lungs — while getting someone to buy into a grand plan like the digital twin has not been easy.

A £5 million grant application in the early 2000s went right to the very top of the Wellcome Trust, one of the biggest funders in the world, but was rejected as too ambitious. “They said, ‘Don’t be ridiculous’. They said, ‘Go away and come back [with something narrower]’. And that’s what we did and they did fund our heart physiome research, but it was devastating at the time. I can remember feeling incredibly dejected.

That changed in 2021, when New Zealand’s Ministry of Business Innovation and Employment committed $15 million over five years for the 12 Labours project. It’s a game changer, Hunter says, the first grant that funds long-term visions, not short-term outcomes.

Since the funding started, there has been solid progress. Hunter talks about “getting more and more optimistic” and about “a reasonable time period” for success.

“I would have a vision now of it being about 10 years to get something that’s extremely useful in terms of real outcomes for medical practices; in terms of being able to base medical decisions on rational understanding of the multiscale modelling framework; on looking at the body through physics and maths, as well as chemistry and physiology.”

In another 10 years, Peter Hunter will be 85. Marco Viceconti in Bologna says the idea his friend and colleague might retire is inconceivable.

“For us, he is eternal. In the last 20 years, he has always looked the same: skinny, tall, and white- haired. We all live under the impression that he is not ageing.

“But because we study living organisms, we do know that this will happen, eventually. And when it does, the best way to celebrate his legacy is to transform, once and for all, the crazy vision of this tall Kiwi into a clinical and industrial reality. A digital model of the entire human pathophysiology? Yes, we can!”

Ask Hunter whether this can be achieved in his lifetime?

“My dad lived to 94. So, I’m reasonably hopeful.”