UTOPIA LAB

THE PROBLEM

The criminal justice system is broken.

New Zealand has one of the highest incarceration rates in the developed world. Around 9000 people are in prison at any one time. That’s just under 200 prisoners per 100,000 people, compared to somewhere between the 30 and 60 in the Nordic countries. This is worse than it used to be: the rate was just 83 in 1980.

The logic behind imprisonment is that it keeps people safe by deterring crime and rehabilitating offenders. But when you dig deeper, there’s little evidence that it actually works that way.

About 60 per cent of New Zealand prisoners will reoffend, and 40 per cent will be reimprisoned within two years of being released. Numerous international studies show that prison only deters offending in certain limited cases — mainly white-collar crime by white middle-class men.

Instead of protecting society by reducing overall harm, prison exacerbates many existing social problems.

Examples include:

– Removing people from employment and their loved ones, damages their communities in the process.

– Exposing inmates to more serious offenders and gang networks in prison can encourage further offending.

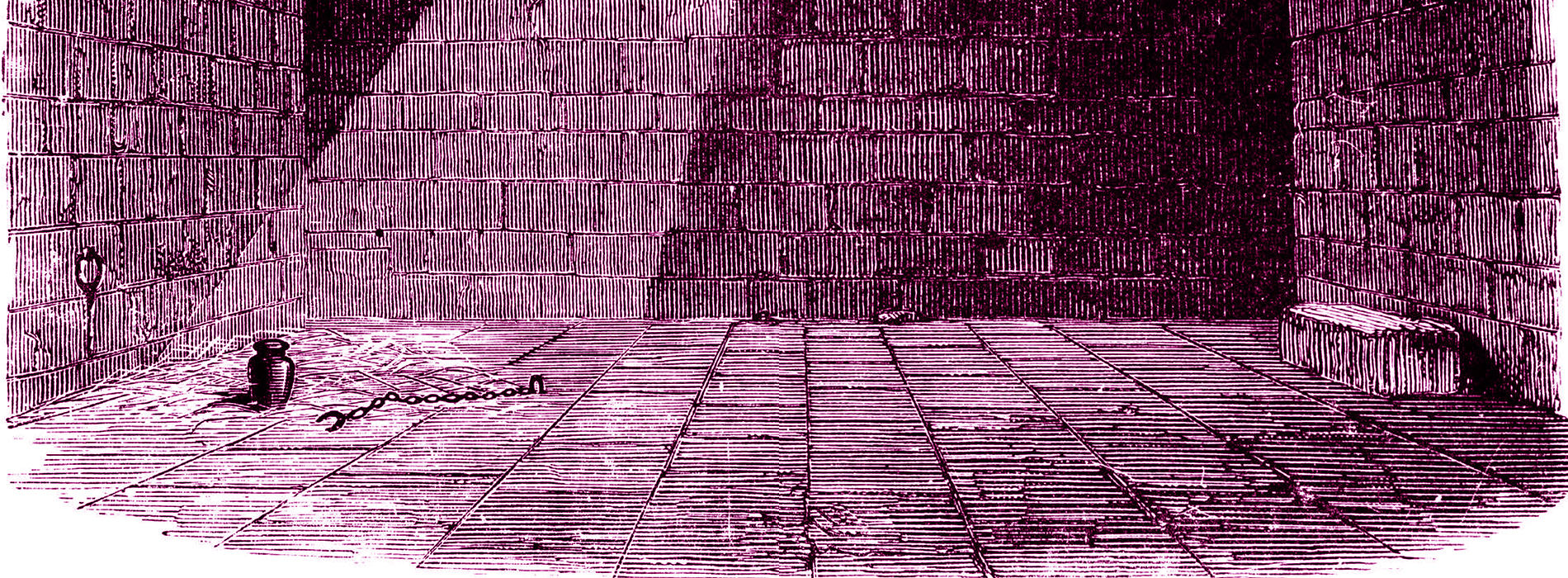

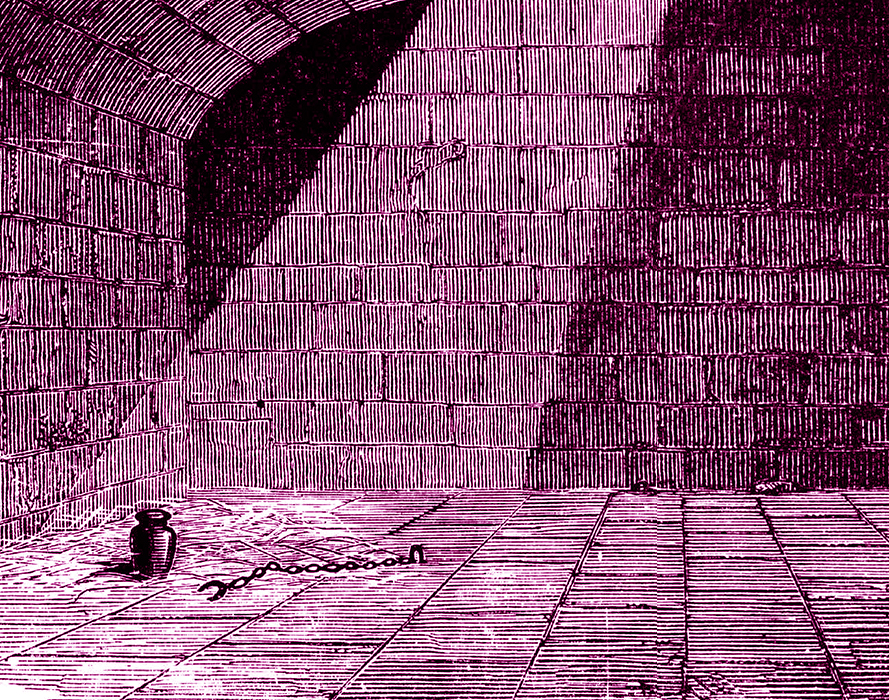

– Inmates are subject to dangerous and dehumanising conditions. A District Court judge recently found treatment at Auckland Women’s Prison to be “excessive, degrading and fundamentally inhumane”.

– The stigma of prison has long term consequences. Ex-prisoners struggle to find stable accommodation and employment, with the vast majority of employers preferring applicants with little work experience over ex-prisoners.

The most marginalised people in New Zealand society are disproportionately affected by our current tendency to overincarcerate. People sent to prison are more likely to be poor, homeless, mentally unwell, and intellectually disabled. Maori make up over half of the prison population but only 16.5 per cent of the general population.

One in three inmates haven’t even been found guilty but are being held on remand while they await a court hearing, often because they lack a suitable address to go to while on bail. Remand prisoners are forecast to outnumber sentenced prisoners by 2029.

THE SOLUTION

Abolish prison as we know it. Seriously.

This may sound drastic — unrealistic even. But Emilie Rākete, a founder of People Against Prisons Aotearoa, says that instead of locking people up we should confront the factors that drive people to offend in the first place, while taking practical steps to address immediate risks to others.

“It is almost entirely New Zealand’s working class who are being sent to prison,” Rākete says. “Since the 1980s, the New Zealand government has deliberately, as a matter of economic policy, created an enormous underclass of people who are desperately poor and have very little or no social safety net by which to sustain themselves.”

Nine out of 10 prisoners suffer from a mental health or substance abuse disorder; a similar proportion were unemployed or relying on the informal economy for the three months before they were imprisoned.

In that light, our response to crime should prioritise in-community therapeutic responses that address these challenges, while also strengthening the social safety net. That includes expanding state housing and mental health services, and boosting benefits to enable everyone to meaningfully participate in society.

But what about violent offenders? Forty-three per cent of the prison population is serving sentences for violent or sexual offences.

“In the immediate term, you have to make sure nobody’s being hurt,” Rākete says. “But that doesn’t mean that people who behave in these ways get put in a concrete cage for years of their lives. Instead, it means taking these people somewhere safe, where they are not going to harm themselves or others, and where their problems can be worked through without putting them on a pipeline to be cycled in and out of prison.”

Finland has taken a step in this direction. It has significantly reduced its prison rates, without crime rising, through greater investment in early intervention, rehabilitation and reintegration, along with more generous income support. The Finnish feel safer for it, too. Surveys show that New Zealanders are much more fearful of crime, even though our crime rates are similar.

Ultimately, Rākete says, the aim should be to transform the social and economic conditions that cause offending in the first place. “This problem will never go away as long as New Zealand’s enormous income inequality persists.”

THE BENEFITS

Victims and offenders would both be better served.

– Ending imprisonment would preserve and strengthen communities across generations because fewer families would be torn apart. A child whose parent is in prison is between eight and 10 times more likely to end up in prison themselves. There are around 20,000 children in New Zealand with an incarcerated parent.

– A greater focus on community rehabilitation could reduce offending and recidivism. The Department of Corrections acknowledges that community-based rehabilitation programmes are twice as effective as prison-based ones.

– A focus on repairing trauma would be better for victims. Currently three per cent of victims experience more than half of all crime; and 77 per cent of people currently serving a prison sentence have themselves been victims of violence including sexual violence.

– The money we spend on prisons could be used far more effectively. The cost of prison has tripled since 1996. Prison currently costs $385 per prisoner per day, compared to $82 for home detention and $26 for community detention. Early intervention programmes in schools and homes, such as cognitive behavioural therapy for preschoolers, have been shown to be more cost effective than imprisonment.

THE OBSTACLES

We think crime is worse than it is.

– In 2016, 71 per cent of New Zealanders thought crime was increasing even though crime rates are at their lowest since the late 1970s. (This may be driven by increased media coverage.) Those least at risk of crime, such as those over 50, are more likely to think it’s rising. Those are the same groups that are most likely to vote.

– The most powerful in society have little connection to the problem. “Rich people almost never go to prison. Most people in prison are poor people. That’s not a coincidence,” Rākete says.

– We keep building prisons. In 2019–20, 318 new prison beds were added.

– Appearing tough on crime can be good politics. National has pivoted to law and order issues several times since being in opposition, with Judith Collins recently criticising the government’s “soft, pathetic approach to law and order”, and saying prison numbers may need to rise.

And while the Labour government has set a target of reducing prisoner numbers by 30 per cent over 15 years, imprisonment remains a key part of the government’s vision for the justice system.

Ollie Neas is a journalist and legal researcher based in Wellington.