BACKSTORY

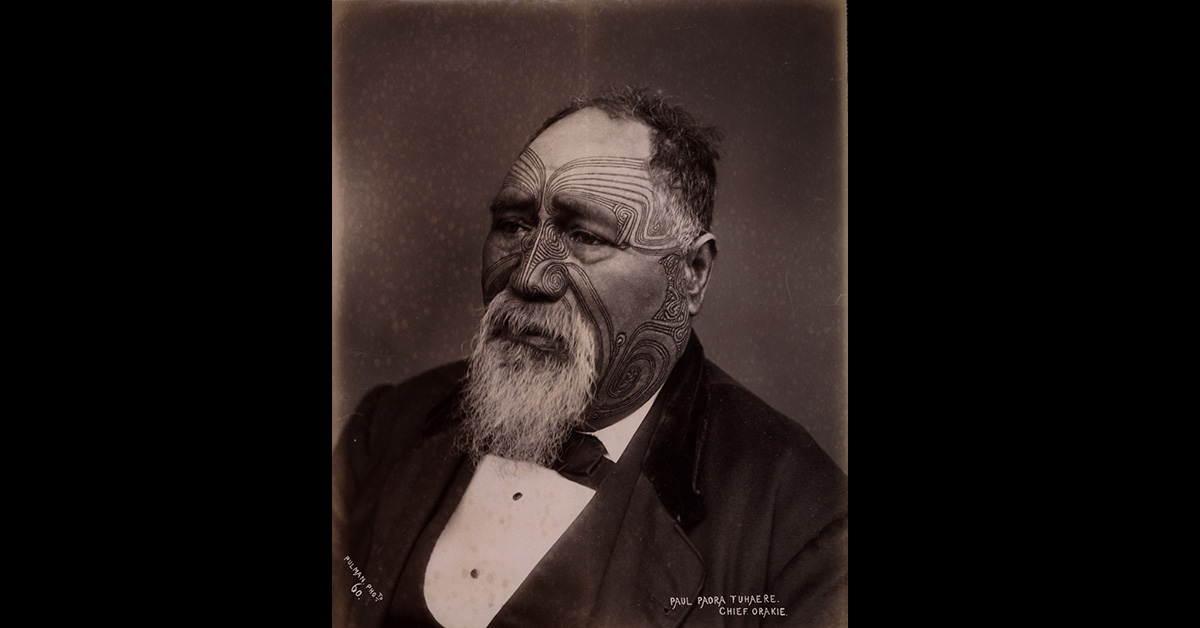

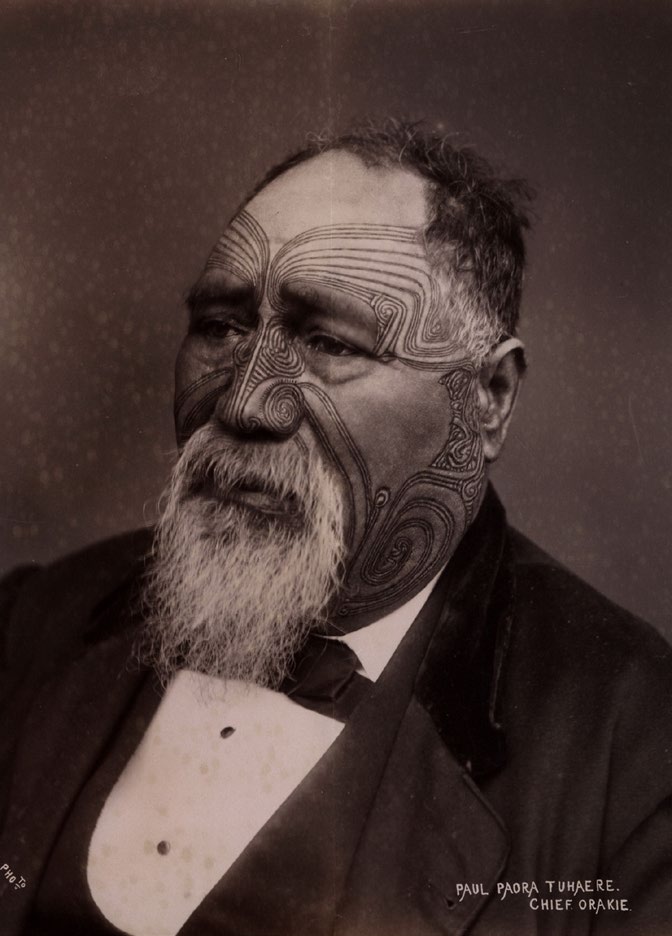

Photo: Paul Pāora Tūhaere photographed by Elizabeth Pulman, via Wikimedia Commons.

Cook Island Connections

A place long seen by many Kiwis as somewhere to head for a “flop and drop” beach holiday, the Cook Islands is rich with tales of adventure and colonial resistance, much of which interlaces with New Zealand’s own history in surprising ways.

By Scott Hamilton

Planeload after planeload of New Zealanders headed for the Cook Islands when quarantine-free travel between the two countries began in May, packing the resorts of Rarotonga and Aitutaki almost to capacity with Kiwis (the bubble was paused following New Zealand’s Covid-19 outbreak in August). Even before Covid-19 severely limited our travel options though, the Cooks have long been one of this country’s most popular winter-holiday choices.

Most New Zealand visitors to the Cooks are prone to seeing the country as a series of beaches and bars. We lie on the sand like prawns on a grill, snorkel over lagoons and reefs, and drink fluorescent cocktails out of coconut shells in sand-floored bars. But what if a visit to the Cooks could be good for our brains as well as our bodies? What if it here could teach us something important about Pacific history and about our own identity?

The Cooks is a small country with a big history. Its Indigenous people have emerged from a long winter of colonisation to find a place in the sun. Cook Island Māori control virtually all their country’s land, populate the public service, and dominate the booming tourism industry.

Both archaeology and oral history connect the Cooks with Aotearoa. Legends say the waka that discovered our nation departed from Rarotonga, and anyone looking at a map of that island can find names which also belong to iwi, maunga, and awa in Aotearoa. Sir Peter Buck found kumara plants identical to those in Aotearoa in a cave on Mangaia, the Cooks’ southernmost island.

There is also a sense in which the Cooks offer an alternate version of the history of our own country. Looking at them, we can imagine an Aotearoa where Māori did not lose land, power, and the demographic advantage in the 19th century. And yet Cook Islanders nearly suffered the fate of their southern cousins.

The Cooks were free of colonialism in 1863, when Ngāti Whātua entrepreneur Paul Tūhaere sailed a 56-ton schooner called Victoria from Auckland to Rarotonga. The Rarotongans had invited Tūhaere to trade with them after hearing about the burgeoning economy of the Waikato, where the followers of King Tāwhiao had planted fruit trees and sown wheat on land that white settlers coveted. Waikato iwi and their allies, including Ngāti Whātua, were getting rich selling food to settlers cooped up in Auckland. The frustrated settlers had demanded the invasion of the Waikato, and by 1863 Auckland had filled with bluecoated British troops.

Tūhaere and his hāpu were given land on Rarotonga, and the Victoria was soon sailing back to Auckland with a load of tropical fruit. When they learned of Rarotonga’s mild climate, volcanic soils, and lack of colonists, Ngāti Whātua leaders began to consider a mass migration. Watching the imperial army pass through Auckland, Tuhaere’s uncle Te Apihei told a hui that he would like to move from his “land of confusion” to the Cooks, “a land fit for orphans and old men”. (Te Apihei decided to stay in Tāmaki Makaurau, and slowly lost his land.)

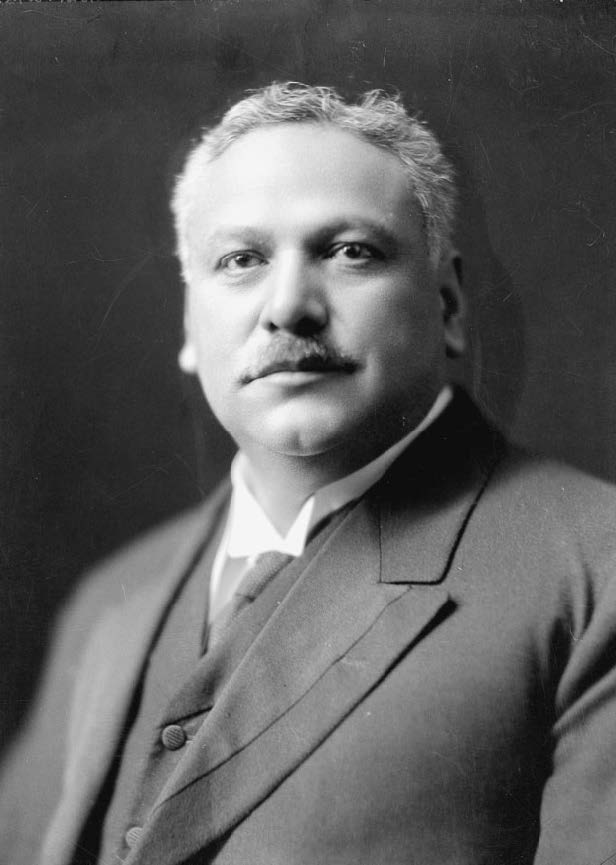

Sir Māui Pōmare, first minister for the Cook Islands. Photo: S P Andrew Ltd,

Alexander Turnbull Library.

One of the passengers on the first voyage of the Victoria had no intention of staying long in Rarotonga. He was Henry Nicholas, a young activist for the Waikato Kingdom. Nicholas’ father was European, but his mother came from Ngāti Hauā, the iwi who had initiated the Māori King Movement, and he was travelling to Rarotonga to buy guns and ammunition for Tāwhiao’s army. Tūhaere for his part was trying to remain on good terms with the Crown, and when he discovered Nicholas’ mission he refused to return the young man to Aotearoa. When British and colonial troops invaded the Waikato in July 1863, Nicholas had to make a new life on Rarotonga. After hearing how the invaders had destroyed the orchards of the Waikato, he decided to recreate the kingdom’s economy in the Cooks, planting tens of thousands of orange trees on Rarotonga. Nicholas then acquired shares in a series of ships and continued the export trade Tūhaere had begun. In the 1870s, Nicholas helped Rarotonga prosper and became a leader on the island.

When France threatened to colonise the Cooks, the islands’ chiefs asked Britain to establish a protectorate. In a deal made in 1888, Britain agreed to defend but not interfere with the islands. A New Zealander named Frederick Moss was sent to Rarotonga to act as a sort of informal British ambassador. Moss was an anti-imperialist, who wanted to see the Cooks develop their own government. He helped set up a parliament for the islands, where elected MPs sat down with chiefs. Nicholas and Moss became close allies, and published a newspaper together, in which they urged islanders not to surrender their land or their sovereignty to Europeans.

When they learned of Rarotonga’s mild climate, volcanic soils, and lack of colonists, Ngāti Whātua leaders began to consider a mass migration.

Moss’ career was doomed when Dick Seddon became New Zealand’s leader in 1893. Seddon was determined to create a New Zealand empire in the South Pacific, and in 1901 he grabbed the Cooks. He sent William Gudgeon, a veteran of several wars against Māori in New Zealand, to govern the islands. Gudgeon’s thick military moustache was seldom disturbed by a smile. He was convinced that Cook Islands Māori were an inferior people who were becoming extinct, and could be replaced eventually by white settlers. Gudgeon dissolved parliament and sidelined chiefs. He opposed the establishment of secondary schools in the islands, insisting that “native boys need to know only enough to garden”. A series of islands revolted against New Zealand rule. In 1908 the people of the northern atolls, Rakahanga and Manihiki, tore down the colonial flag, proclaimed their own government, and called for Gudgeon’s death. The governor visited in a cruiser, landed with a force of marines, then tried and convicted his critics at gunpoint, sentencing them to forced labour on Rarotonga.

Following New Zealand’s 1911 general election, Māui Pōmare became minister for the Cook Islands. Although Pōmare was a very moderate figure within Māoridom, urging his people to assimilate to the Pākehā world, he remembered the tragedies of the 19th century, and did not want the Cook Islanders to lose their land to settlers in the way his tīpuna had. Pōmare sacked Gudgeon, making the hated governor pay for his boat ride to Auckland. Pōmare and other Māori MPs then helped push the Cook Islands Act, which guaranteed Indigenous control of land, through Parliament in 1915.

Cook Islanders kept their lands, but New Zealand spent little on the country’s development, and most islanders lived in poverty as subsistence farmers and part-time workers. Some began to migrate to New Zealand in search of work and money. One of them was Albert Henry, a young man from Aitutaki who arrived in Auckland near the end of World War II. In Auckland Henry met and befriended the communist trade unionist Pat Potter and the communist poet RAK Mason. With their help he founded the Cook Islands Progressive Association (CIPA).

By 1947, the CIPA had 3000 members on Rarotonga and was leading the island’s waterfront workers, orange packers, and nurses in a strike for better wages. Thanks to Potter and Mason’s lobbying, the crews on New Zealand ships visiting Rarotonga went on sympathy strikes. When two CIPA members were arrested on trumped-up charges, a crowd marched to Rarotonga’s police station and laid siege to the building until the men were released. New Zealand Prime Minister Peter Fraser was alarmed by the turmoil. The Cold War had begun, and Fraser was convinced that the CIPA was part of a Soviet plot to destabilise the South Pacific. He sent a force of armed police to occupy the waterfront on Rarotonga. In response, thousands of Rarotongans descended on their port and locked arms around it.

By 1949, Rarotonga’s wharfies had won their demands for a better wage. After summoning Albert Henry to Wellington and realising that he was not, in fact, a KGB agent, Fraser gave the CIPA a loan to buy a trading boat. In 1965 Henry became the leader of an independent Cook Islands; he ruled until 1978.

Recently I sat with Albert Henry’s grandson on a veranda above a beach on the south side of Rarotonga. Howard Henry has spent his retirement years researching and writing about the Cook Islands’ long struggle to remain independent. “We are lucky,” he told me. “We could easily have ended up like Henry Nicholas’ tribe in the Waikato. Gudgeon wanted us off our land, but Pōmare stopped him.”

Henry is proud of his grandfather, and of his country’s achievements since 1965. “We’re now the third-richest country in the Pacific, after Australia and New Zealand,” he said. “When I grew up, most houses here didn’t have electricity or running water.” And yet, he added, the Cooks have many problems. “We remain dependent on the big countries. There are 60,000 of us in New Zealand and only 17,000 here. The young people find it hard to come home and get decent jobs.” The minimum wage in the Cook Islands is only eight dollars an hour, and Henry says the resort owners import workers from Fiji and the Philippines because locals don’t want to work for so little. As its economy grows, will the Cooks cement some of the inequality and meanness of wealthy Western countries, or will it continue to surprise?

Scott Hamilton has a PhD from the University of Auckland and is a published historian. His last column for North & South looked at New Zealand’s history of public toilets.

This story appeared in the September 2021 issue of North & South. It has been amended to reflect that the conditions of quarantine-free travel were changed following New Zealand’s Covid-19 outbreak in August 2021.