BACKSTORY

In July 2016, then-US vice president Joe Biden talks with Government House kaumatua Lewis Moeau. Photo: RNZ / Claire Eastham-Farrelly.

From America With Love

A promising start with the Biden White House is just the latest twist in the US-New Zealand relationship.

By Scott Hamilton

Not long after Joe Biden’s victory last November in the US election, he called Jacinda Ardern to say he wanted to “reinvigorate” the relationship between his country and New Zealand. On a visit here in 2016, when he was vice president, Biden told reporters that America and New Zealand were “cut from the same cloth”. He explained that two of his uncles fought in World War II, and that he had grown up hearing stories about the toughness and bravery of New Zealand soldiers.

The US and New Zealand do indeed have a long history — one that goes back almost as far as our country’s history with the British but is far less understood. American whalers began to visit these islands in the 1790s; they were soon followed by sealers. Unlike the British, who could base themselves in Sydney or, later, Hobart and Melbourne, the Americans were far from home ports, and often spent months in our harbours and estuaries, relying upon the hospitality of Māori communities. They would pay a “tariff” of tobacco or guns to a local rangatira in exchange for the right to anchor and to hunt. They hired local Māori to fill out their crews. They communicated through local interpreters, who were known as “tonguers” because they were paid for their services with the tongues of slaughtered whales.

Whaling and sealing were hard and dangerous jobs, and many captains governed with whips. Soon Americans were deserting from their ships, taking Māori wives, and settling in coastal kainga. Some became tonguers themselves. Others learned to live from the land and the sea. In the far south of Te Wai Pounamu there were so many deserters that Ngāi Tahu chiefs offered them an island to live on. Māori called the sanctuary Whenua Hou, or the New Land. The deserters and their wives planted subsistence gardens, gathered shellfish, and hunted birds.

When he excavated Whenua Hou, archaeologist Ian Smith discovered that the island’s settlers had built European-style homes, with timber slats and A-frame rooves, but had cooked their food outside, in the ground, like Polynesians. Between 1823 and 1850 at least 33 men, 24 women, and 40 children lived on Whenua Hou. Years before the Treaty of Waitangi was signed, these Pākehā and Māori were creating a hybrid culture.

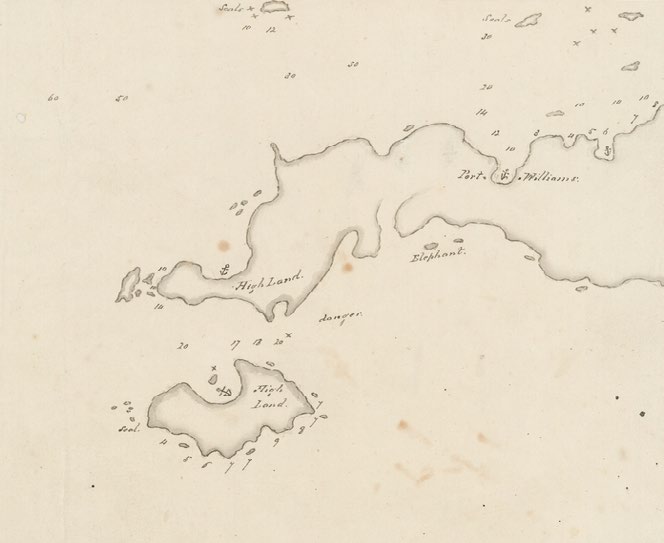

Part of an 1808 map of the Foveaux Strait region, showing Whenua Hou island. Photo: State Library of New South Wales.

By the 1860s American whalers had begun to worry New Zealand’s British administrators. Much of Te Ika a Maui was at war, as Māori resisted the British invasion of the Taranaki and Waikato. Pro- and anti-colonial factions fought inside iwi like Ngāti Porou. Māori needed guns, and Americans often armed the anti-imperialist side in New Zealand’s wars. In 1865, Thomas Bateman, the collector of customs at the port of Russell, complained that “natives” were “obtaining large supplies of arms and ammunition” from American whalers. In the same year, Bateman’s counterpart in Auckland reported that “warlike stores” were moving from “American” ships to “natives on the East Coast”.

The United States was also at war in the 1860s, and Lincoln’s struggle against the 11 secessionist slave states both fascinated and agitated New Zealanders. Outside of Auckland, almost all of the colony’s newspapers and politicians sided with the Confederate states. Sympathy was especially strong in the South Island, where many settlers wanted a secession of their own. In October 1861, seven months after the beginning of the war, Lincoln’s navy stopped a British steamer and seized two Confederate envoys who were travelling on it to Europe. Britain was outraged, and threatened to enter the war on the Confederate side.

News of the crisis only reached New Zealand in January 1862, and settlers decided that the British Empire must already be at war with the northern states. Many feared that Lincoln would send ships to raid the gold-rich city of Dunedin. The Otago Witness warned of “privateering or buccaneering expeditions . . . fitted out in Californian ports”. At a public meeting in Dunedin, 43 men pledged to form a militia that could fight Lincoln’s raiders. More soon joined them, and the name Otago Volunteer Rifle Rangers was coined.

Only with the belated arrival of a mail ship in March did New Zealanders learn that Lincoln had backed down, released the Confederates, and patched things up with London. Otago’s Rangers cancelled their drills.

After the American Civil War ended in 1865, some of its veterans migrated to New Zealand. They did not always forget their old causes. The poet Kendrick Smithyman grew up in the 20s in the small Northland town of Te Kōpuru, where his parents ran a retirement home. Two of the home’s inhabitants were veterans of the American war. Smithyman remembered how, whenever they came across one another in the hallway, the northerner and the Confederate would duel with their walking sticks.

New Zealanders may have been less friendly if they knew Americans were drawing up a 62-page plan for the conquest of Auckland.

The defeat of the Confederate cause did not end New Zealanders’ sympathy with the American south. Minstrel shows, which mocked African-American culture and presented a sentimental picture of slavery and the south, became popular in New Zealand. In 1877, a group called the Georgia Minstrels toured the country, playing to big crowds. An excited Evening Post told its readers that the troupe’s members were “real negroes”, who were “well up in n***** business”. Amateur minstrel groups were formed in many towns and villages. They performed in blackface at fairs and charity concerts and on parades.

Sometimes the ethnic conflicts of America echoed in New Zealand. In 1908, Jack Johnson became the first black heavyweight boxing champion of the world. From Australasia to America to Europe, Johnson’s victory was seen as a threat to white power. Jack London, who had watched the fight, called for a white boxer, a “great white hope”, to “rescue” his race by defeating Johnson.

New Zealand’s Truth newspaper called Johnson a “dandy coloured coon”, and complained that, after his victory, non-whites “swaggered up and down Queen Street like emperors”. A black Aucklander who had the misfortune to be named Charles Johnston was attacked by whites a few days after the boxing match. Johnston defended himself with his cane, and was convicted of assault and fined five pounds. The Truth gloated that his fate would “take some of the swagger out of the coon brigade”.

In 1915 a neo-Confederate film maker released The Birth of a Nation, an advertisement for slavery, the secession, and the Ku Klux Klan. In America, the movie helped revive the Klan; in New Zealand it was also a hit, and prompted a craze for dressing in white sheets. Kids went as Klansmen to fancy dress dances, and in 1923 Auckland University students celebrated their graduation by donning white robes and riding horses round the city. By the end of 1923, real-life Klansmen had claimed responsibility for the burning of two shops in Mount Eden and the vandalism of an Indian business in Christchurch. Despite a few violent incidents, the Klan did not establish a lasting presence in New Zealand.

In 1909, the Great White Fleet steamed into Auckland’s Waitemata Harbour. The fleet got its name from the colour of its battleships. There were 16 of them, and they carried 14,000 men. President Teddy Roosevelt had sent the fleet on a round-the-world journey, to show off his country’s might and intimidate its new rival, Japan.

One hundred thousand Aucklanders turned out to welcome the Americans. They may have been less friendly if they knew that the visitors were reconnoitring their city and drawing up a 62-page plan for its conquest. Britain had signed a defence treaty with Japan, and New Zealand was a part of the British Empire. If America went to war with Japan, then it might have to fight against New Zealand too. The American attack plan, which was only revealed in 2006, called for heavy guns to be landed on Rangitoto, so they could shell naval bases on the North Shore, and for troops to make a surprise landing on a remote part of the Manukau Harbour.

American forces did eventually land on our shores in the winter of 1942, but for a very different purpose. By then, Britain and the US were fighting on the same side of a war against Japan. Tens of thousands of Americans arrived to recuperate from battles against Japan in the Solomons and to train for the reconquest of the tropical Pacific. This period is often remembered as one in which American servicemen charmed Kiwis with their popular music (and charmed Kiwi women with their more chivalrous manners), but it had a darker side, too.

Some of the American deserters were hidden by local women.

Many of the American soldiers had grown up in southern states; soon they were trying to force strict racial segregation on New Zealanders. Māori servicemen were denied drinks by American mobs at bars, and thrown off trams. Māori and many Pākehā objected. In October 1942, Māori and American servicemen fought in central Auckland; one American had his skull broken, and died in hospital. In February 1943, American and New Zealand troops opened fire on each other with revolvers in Auckland’s Shortland Street; two men were taken to hospital.

The most famous confrontation came in April 1943 in Wellington, and was nicknamed the Battle of Manners Street. A group of Māori servicemen entered a bar where Americans were drinking. They were called “black curs” and thrown out. Soon a thousand American and New Zealand soldiers were fighting with belts, knives, and bottles. American military police arrived and, instead of arresting their own men, attacked the New Zealanders with their batons. Historian Redmer Yska believes that at least two and possibly many more Americans died on Manners Street.

Not all the American servicemen disliked New Zealand. Some were so taken with the country that they deserted the army, much as whalers and sealers had once deserted their ships. Some of the deserters were hidden by local women. Military police hunted for the soldiers, but by the time the American army left New Zealand in late 1944, 200 were still unaccounted for. The spirit of Whenua Hou persisted.

American soldiers, Oriental Bay, Wellington, 1943. (Alexander Turnbull Library).

Scott Hamilton has published books about the Pacific slave trade, the Great South Road, and British socialism.