BACKSTORY

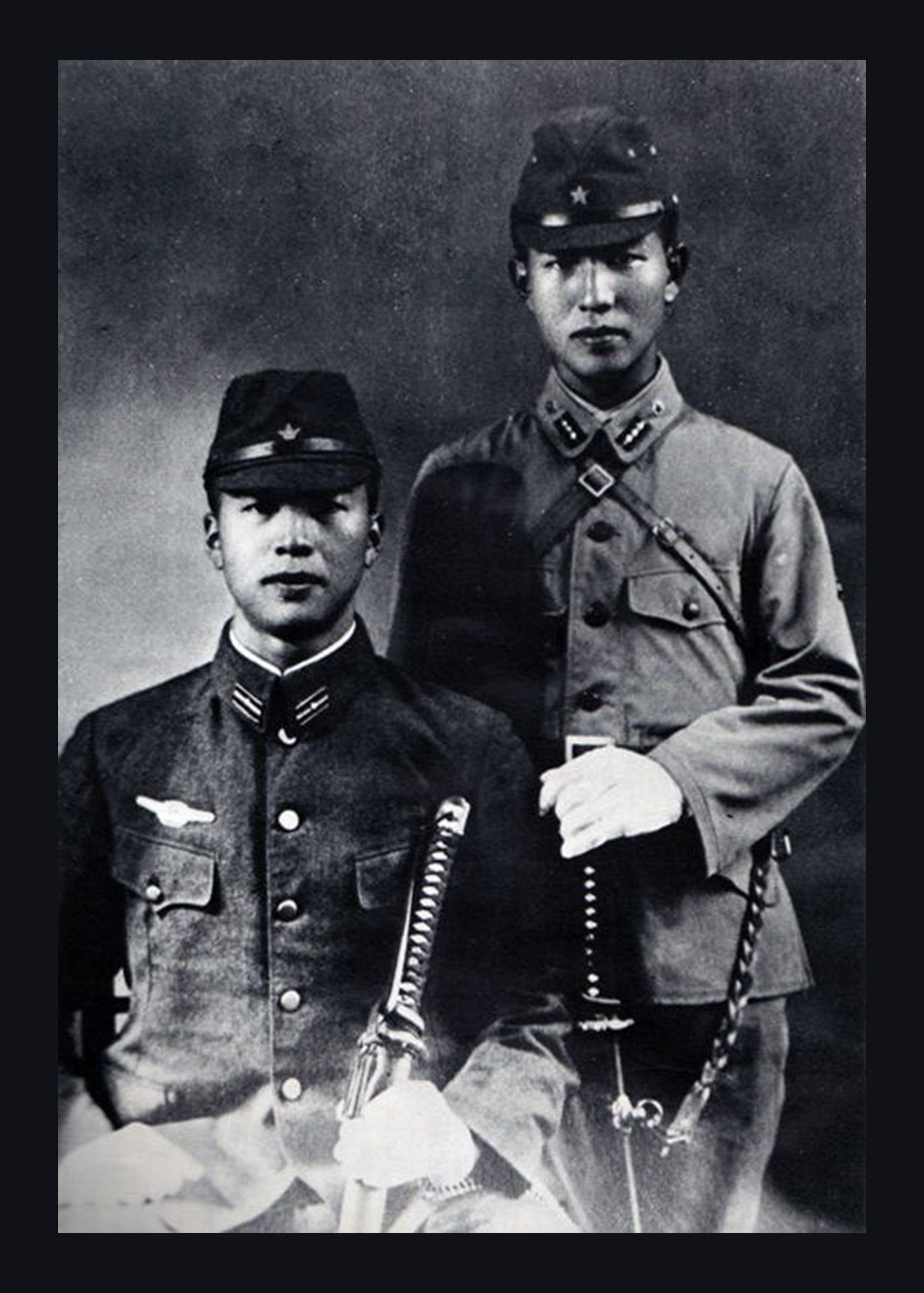

Famous Japanese “straggler” Hiroo Onoda (right) and his younger brother Shigeo Onoda, circa 1944. Photo: Wikipedia.

Gone Bush

To evade New Zealand’s draft in both world wars, scores of conscientious objectors fled deep into the bush. There, they hid from the authorities — sometimes for years.

By Scott Hamilton

When World War II ended in 1945, hundreds of Japanese soldiers refused to put down their guns. Isolated on Pacific islands, they could not believe that their emperor had surrendered. They took to the jungle, living in huts and caves and raiding villages for food. These diehard warriors became known as stragglers. The most famous straggler was Hiroo Onoda, who hid in the forests of the Philippines’ Lubang Island for 29 years. Onoda surrendered only when his former commander, who had become a bookseller in peacetime Japan, visited Lubang to assure him that the war was over.

After both world wars New Zealand had its own strange stragglers. Whereas the Japanese stragglers refused to accept peace, our version hid from war.

In 1916, two years into World War I, New Zealand’s Parliament passed the Military Service Act, which obliged non-Māori men between the ages of 20 and 46 to register for service. In 1917 the law was extended to Māori.

Conscription was necessary because many New Zealanders were reluctant to join the war. Leaders of trade unions and the nascent Labour Party opposed the conflict, seeing it as a squabble between Europe’s rich men. In 1916 Irish nationalists had staged an Easter Rising against British rule and the war; many members of New Zealand’s huge Irish population sympathised with the rebels, and wondered why they should fight for an empire that had long oppressed their kin.

The same sort of question was asked by Princess Te Puea Hērangi, a leader of the iwi of the Waikato. Te Puea urged the young men of her rohe not to fight until the Crown made recompense for the invasion and theft of their lands in the 1860s.

But any eligible man who refused to register for service risked imprisonment for two years, with hard labour. War refusers also risked vilification. Newspapers called them defaulters, shirkers and funkers; the newly formed Returned Soldiers’ Association accused them of cowardice and treachery.

Some war resisters fled to Australia, where conscription was never introduced. In the South Island, a sort of underground railroad helped refugees escape. Young men from Christchurch or Dunedin would hike into the Alps, where Irish publicans in gold-mining towns would hide them and tell them about tracks that led over passes to the West Coast. In ports like Hokitika and Greymouth, sympathetic wharfies and seafarers would smuggle the refugees aboard boats bound for Australia.

But some young men became inner émigrés, exiles in their country. They left their cities and towns for the mountains and bush, where they established camps far from roads and the threat of arrest. Many fished and hunted for food. Some rustled sheep and cattle from remote farms. A few had confederates in the towns, who would quietly bring them food and news.

Unlike the Pākehā pioneers of the earlier century, these young men did not want to make their mark on nature. They hid amongst trees, rather than felling them. They brought no theodlites, and raised no fences.

Willis’s hair ran to his shoulders; his beard reached his belt; his clothes were rags. A newspaper report says that the hunters were excited to catch ‘a real wild man’.

In 2016, a century after the introduction of conscription, journalist Georgia Weaver visited a site called Shirkers’ Bush, near an alpine lake on the Southland–Otago border. She found fragments of a refugee settlement: a charred stone oven, a blunt axe head, sheets of twisted rusted iron. Shirkers’ Bush is one of 48 former war resisters’ camps that have been found in Southland.

Some of the exiles enjoyed their new lives. A man named Kiely went into the bush near Blackball in 1917 with two other war resisters. For months they lived in a tent, and spent their days “pottering and prospecting”. The three men became the “best of friends”, and never had a dispute of any kind, Kiely said. But Kiely emerged from the bush after one of his friends was killed by a falling branch. He brought the body back to civilisation, and was promptly arrested.

The war ended in 1918, but punishments for war resisters remained on the books, and young men remained in the bush. In 1920 a group of vigilantes on horseback ran down Harry Willis, who had been living alone in the mountains between Waiouru and Napier for four years, surviving by stealing from sheep stations. Willis’ hair ran to his shoulders; his beard reached his belt; his clothes were rags. A newspaper report says that the hunters were excited to catch “a real wild man”. The war had been over for nearly two years, but Willis was arrested and tried.

Near the end of 1920 Prime Minister William Massey announced an “armistice” with the bush exiles. Too many men were hiding in the hills, when they should be doing productive peacetime work.

By the time World War II began in 1939, several men jailed for refusing conscription in the earlier conflict were members of the Labour government. One of them, Peter Fraser, would soon be prime minister. But Fraser and his colleagues introduced conscription in 1940, and a new generation of men took to the bush. Some of their digs were impressive. In 1943 a party of policemen arrested a group of war resisters in the King Country’s Pukemako district. The men had built a hut from corrugated iron and canvas, and disguised it with branches. They had a radio, a supply of recently published magazines, and a liquor still. The cops confiscated 79 bottles of spirits.

Some war resisters tried to find a wilderness in the city. The brothers Frederick, Reginald and Robert Radermacher set up camp in a block of bush in the Auckland suburb of Orakei. They were caught after sneaking out for a swim in the nearby Purewa Creek.

Other resisters adopted new identities, so that they could live ordinary lives in towns and cities. But new identities could bring new problems. In 1941 Aucklander Charles Brady was called up by the army. Brady had found a levy book that belonged to an enlisted soldier called Howe; he began to use this man’s name, and got a new job among strangers at Auckland’s sugar mill. In 1944, though, Howe deserted from the army. Police went hunting for Howe, and arrested Brady.

World War II ended in August 1945, but in late September the New Zealand Herald reported that many men were still hiding in the backblocks. Their numbers were estimated “to run well into three figures”, and they were raiding granaries and henhouses at night.

None of New Zealand’s world war stragglers stayed at large for as long as Hiroo Onoda. But some of our 19th-century war refusers spent decades in hiding. In 1863 the British ship Orpheus, which was bringing soldiers to join the invasion of the Waikato, got caught on the sandbar at the heads of the Manukau, and was ripped apart by huge breakers. Official figures say that 189 of the 259 men aboard the ship died. But dozens of soldiers and sailors who survived the disaster, floating to remote beaches on spars and logs, chose to play dead. John Kilgour, a farmer and friend of Waikato Māori, hid many of these men on his property at Cornwallis. When army and police patrols appeared, Kilgour sent goats with bells round their neck running through his paddocks. Hearing the bells, the deserters would take cover.

In the 1920s newspapers began to run articles about elderly Orpheus deserters. One of them, James Mason, had spent decades working in the remote gumfields of Northland, far from police stations and army barracks. Mason built a house of corrugated iron at Ngataki, a lonely spot near Cape Reinga. A photo survives of the Bay of Islands MP Allen Bell visiting the old deserter’s shack. Mason peers apprehensively from his doorway towards the visitor. Perhaps he still feared punishment.

Above – Princess Te Puea Herangi was against the men of her rohe fighting in the colonists’ war. Photo: Wiki Commons.

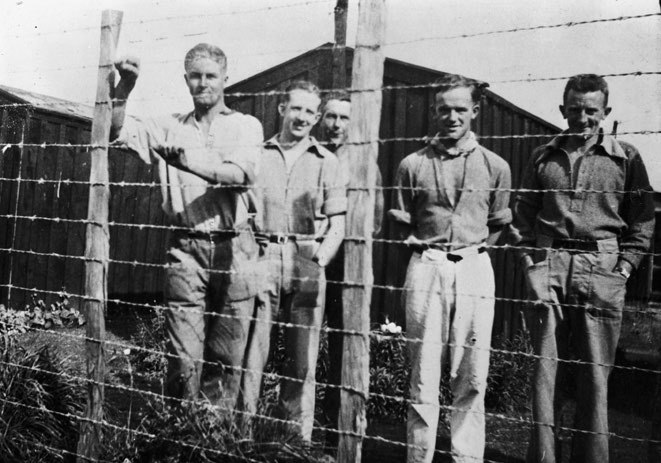

Conscientious objectors behind a barbed wire fence at Hautu Detention Camp, Taupō district, 1943. Photo: Alexander Turnbull Library.

Scott Hamilton is North & South’s history columnist.