UTOPIA LAB

THE PROBLEM

New Zealand has been derailed.

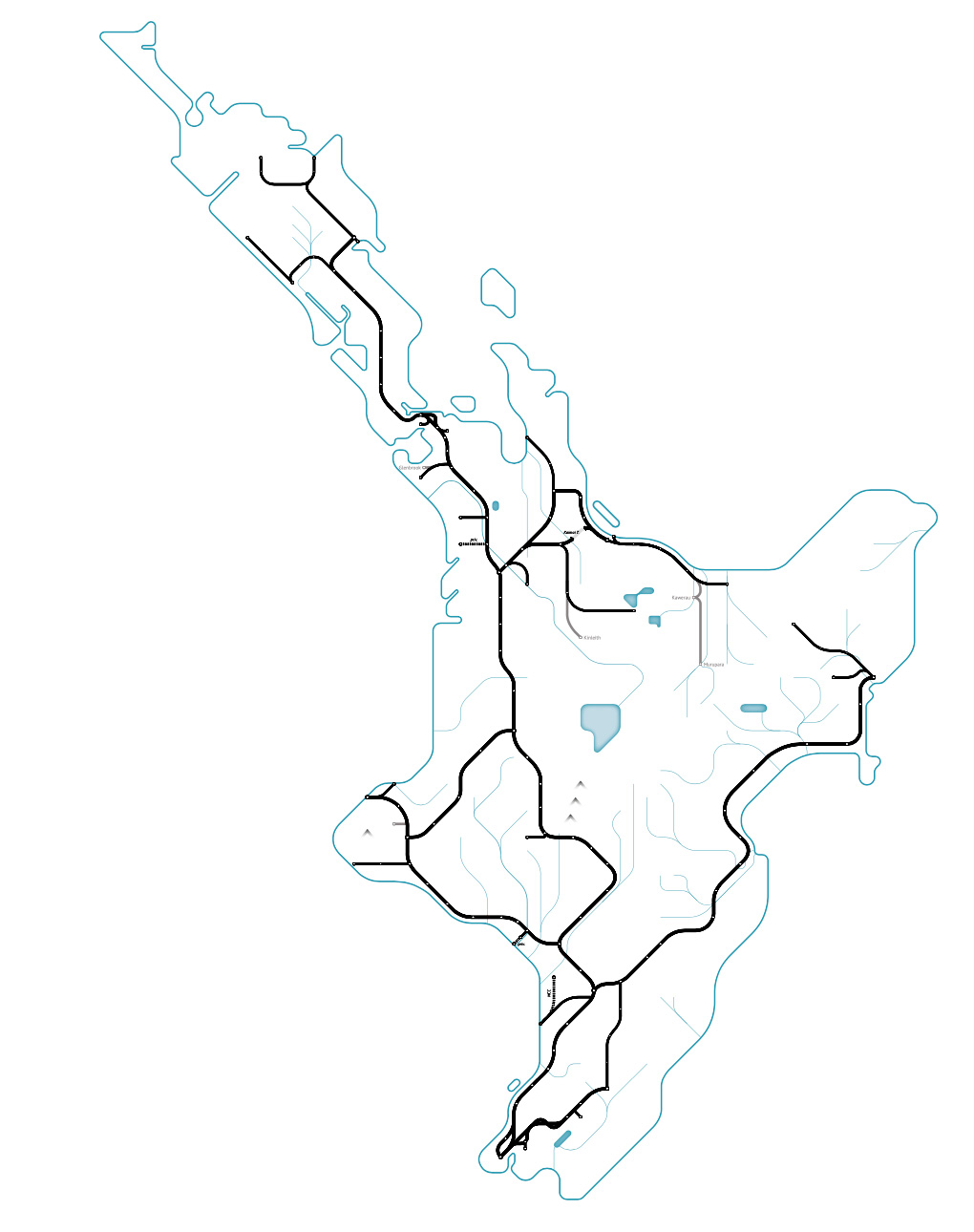

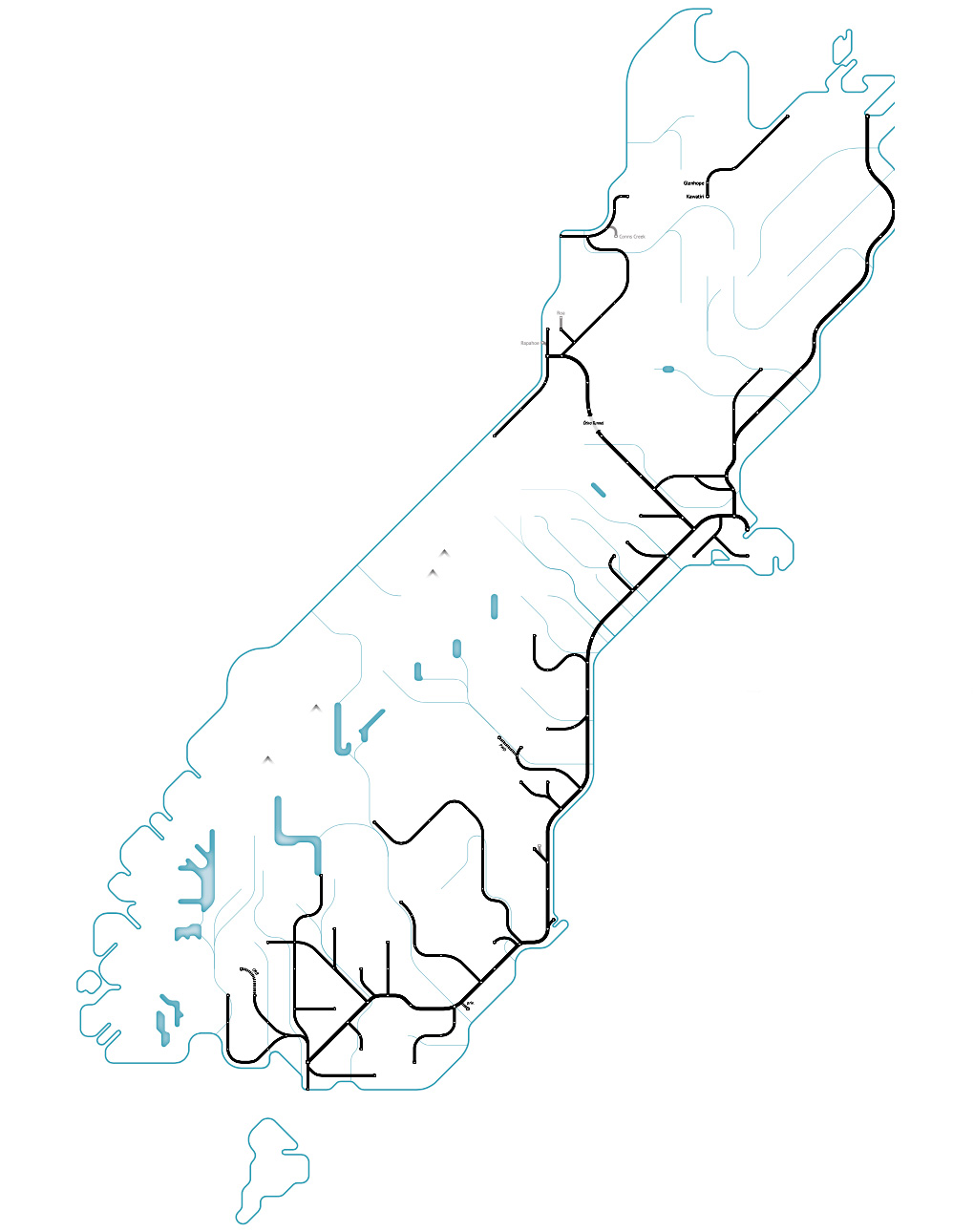

In the 1920s, you could get almost anywhere by train. But a hundred years later, there is just one inter-regional commuter rail service in the entire country, between Palmerston North and Wellington. The few other intercity services are targeted at high-end tourists, making them too expensive and irregular for ordinary people. And the rail network has fallen into disrepair after decades of deferred maintenance — making train services slower.

Meanwhile, New Zealand has gone big on cars and motorways. In 2017 we led the OECD in car ownership; the number of vehicles rose by half since 2000. This is no accident: our transport system is biased toward roading, in the view of the Productivity Commission. This is not just a problem for trainspotters:

– The young and elderly, people with disabilities, and those who can’t drive are poorly served by the status quo. Many small towns are not connected by air travel, and the bus network is uncomfortable and unreliable.

– Transport was the fastest growing emissions source between 1990 and 2016, and road transport is the dominant source of transport emissions.

– Roads are becoming increasingly congested as more freight shifts from rail to road.

– Vehicle pollution causes 256 premature deaths a year, according to a 2012 study.

Historical passenger rail of Te Ika-a-Māui and Te Waipounamu: This map shows every rail line in New Zealand’s North and South Island that carried passengers at some point between 1920 and now. Illustration: Sam van der Weerden, caffeinatedmaps.com

THE SOLUTION

Trains — lots of them.

Historian Dr André Brett is writing a book on the decline of New Zealand’s passenger rail network. In our history, he sees inspiration for a future in which rail once again serves as the backbone of the national transport system.

The aim, Brett says, shouldn’t be the world’s fastest bullet trains but services that are quick, regular and reliable enough to be as attractive as their alternatives. This means:

– Upgrading rail infrastructure to overcome decades of underinvestment. “It’s as if we hadn’t upgraded our highway system for 70 years. That would be a national scandal — and the state of the railways should be a national scandal.”

– Investing in new technology such as tilt trains to achieve speeds of 160 kilometres on our relatively narrow tracks. “If Queensland can do it, why can’t we?”

– Integrating rail with other modes of transport. “It’s not just about trains — it’s interconnection with bus, cycleways, walkways, with all modes of transport.”

– Electrifying the network. “If we’re just building more diesel trains, we’re not maximising our own clean energy resources.”

A starting point could be high-speed rail throughout the Golden Triangle of Auckland, Hamilton and Tauranga — an area with more than half the country’s population. Fundamentally, this shift requires rethinking rail as a public service — not a money-maker. Brett points out: “We almost never ask a road to turn a profit, and yet we judge rail in a completely different way.”

THE BENEFITS

Revitalised regions, clean transport.

– An expanded rail network would make travelling the country more convenient, comfortable and accessible.

– Emissions would fall, helping meet climate targets. A tonne of freight moved by rail produces a third of the emissions as a tonne moved by heavy road freight.

– Improved mobility could revitalise regional communities as tourist destinations and local hubs — and bring jobs. Forty years ago KiwiRail had 22,000 employees but now has around 3400.

– Road safety would improve as traffic shifts to rail. Rail already eliminates around 271 road accidents a year.

THE OBSTACLES

We’re too pessimistic.

Our rail ambitions are being thwarted by unquestioned assumptions that need to be confronted, Brett says. These include:

– New Zealanders are too attached to their cars to embrace alternatives. “There’s not some innate aspect of the New Zealand psyche that makes us love cars. Auckland was a public transport city before it became a gridlocked city, and it can be a public transport city again. The same could be said for elsewhere in the country.”

– Our low population density makes rail untenable. “Density doesn’t have to be the problem people think it is. The more important thing is accessibility. If your public transport is accessible, people will use it.”

– Passengers get in the way of freight, which is where the money is. “Surely the obvious answer is to build more passing loops. Why would we let an opportunity for clean and efficient transport go for want of some passing loops or some doubletrack?”

Cost is another barrier. The Green Party’s plan last election for an intercity commuter rail network was costed at $9 billion. “If we want mobility for everyone that is clean and efficient and multimodal, we are going to have to incur these expenses,” Brett says. “We can’t just keep building roads and hoping that the occasional band aid solution on public transport will cut it.”

Maps from Can’t Get There From Here: New Zealand’s shrinking railway, 1920–2020 by André Brett, Otago University Press. Available in November.

Ollie Neas is a journalist and barrister based in Wellington.