BACKSTORY

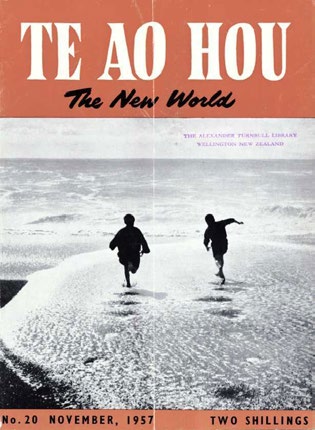

Te Ao Hou cover: National Library of New Zealand.

Gumdiggers and Nude Trampers

We aren’t the first New Zealanders to embark on domestic adventures after being deprived of travel abroad.

By Scott Hamilton

Late last winter, at Auckland airport’s domestic terminal, unusually long queues had formed at the check-in counters for airlines serving the Chathams archipelago and Great Barrier Island. In the queue for Air Chathams, I noticed two men wearing Hawaiian shirts, stubbie shorts, and jandals. A teenager stood behind them, waiting to check in his surfboard.

With their indigenous Moriori culture and spectral landscapes of peat bogs and eroded volcanoes, the Chathams are a wonderful place to visit. They are not, however, a substitute for Hawaii or Rarotonga — more typical destinations when we were able to travel beyond New Zealand’s borders. The Chathams’ beaches are long and lovely, but their sand is cold. The surf may be perfect, but it is patrolled by great white sharks.

We are not the first New Zealanders to be suddenly deprived of international travel and to turn to domestic adventures. In the first decades of the 20th century, upper- and middle-class Kiwis were often able to afford cruises around the tropical Pacific and extended visits to the “home country” of Britain. Poorer New Zealanders could work on the ships that connected their country with the world’s markets, or migrate to more prosperous nations like Australia or the United States.

But the Great Depression trapped most New Zealanders in their own country. Fewer Kiwis could afford long sea voyages. As nations raised trade barriers and bought less from abroad, fewer ships plied the seaways. And as most Western nations toughened their immigration laws, fearing foreign competition for already scarce jobs, the mobility of workers was greatly restricted.

This sudden isolation paid a literary dividend as a generation of New Zealand writers turned their attention to their own country’s hinterlands. The texts they produced are still enjoyable today — and especially relevant now that we are once again shut off from the world.

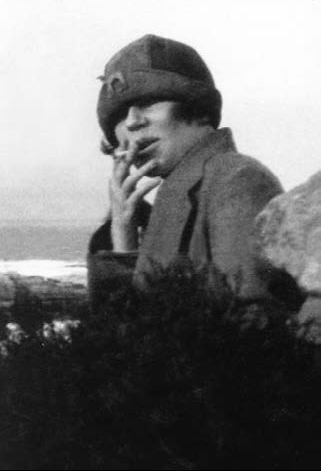

In the autumn of 1937, Robin Hyde found out just how difficult international travel had become. For several years Hyde had lived as a voluntary patient at Auckland Mental Hospital, banging out journalism, novels, and poems on the typewriter in her attic room. But after the departure of a favourite doctor and rows with hospital staff, Hyde fled without warning. Wanting to get as far from Avondale as possible, she was horrified to learn that a one-way ticket to the tropical Pacific would absorb almost all of her writer’s savings. Britain might as well have been another planet.

Frustrated, Hyde headed for the nearest available wilderness — the Waitakere Ranges, which make a green wall between Auckland and the Tasman Sea. She rented a hut surrounded by trees and plaintive kererū, and began to type the memoir she called A Home in This World. For Hyde, the kauri and taraire forests were as exotic as the Amazon. The “cold air” had a “non-human enchantment”. She wondered at rata vines, with their “blotch-blossoms of hairy red”.

On previous, temporary, absences from the asylum, Hyde had written a series of articles called “On the Road to Anywhere: Adventures of a Train Tramp” for the New Zealand Railways Magazine, which was the 1930s equivalent of an airline’s in-flight journal. Catching train after train from one provincial town to another, Hyde glimpsed worlds that seemed strange to her middle-class Pākehā eyes. Passing by the main street of a Northland town, she noticed “gas lamps, countless dogs, and Māori boys wearing magenta blazers plus peppermint-pink berets”. Further north, she paused long enough to describe the hybrid Dalmation-Māori culture that had evolved amongst gumdiggers. As they worked for decades in the mud of kauri swamps, the two peoples learned one another’s songs and stories, and began to converse in a pidgin language. This impoverished bicultural utopia withered when the gumfields closed; Hyde’s prose remembers and celebrates it.

Covers: New Zealand Electronic Text Collection.

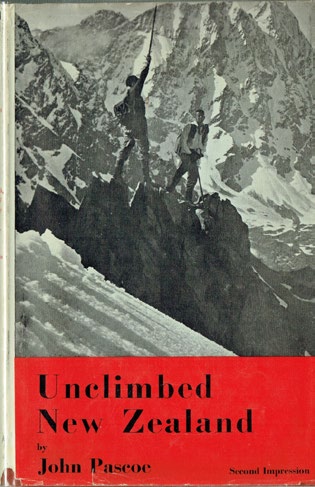

John Pascoe was only interested in rail lines that led to mountains. He was part of a generation of young Christchurchers who would flee the city on Friday afternoons, catch trains to Springfield, at the foot of the Southern Alps, or to Otira, deep in Arthur’s Pass, and pitch tents, ready for a weekend of climbing. During the 30s, Pascoe and other members of the Canterbury Mountaineering Club scrambled up dozens of previously unconquered peaks, as he describes in his 1939 book Unclimbed New Zealand.

Like many of Canterbury’s mountaineers, Pascoe loved poetry. He and friends like Denis Glover would recite Coleridge and Byron to one another as they huddled beside campfires on high ledges. Unclimbed New Zealand sometimes reads like an extended prose poem; Pascoe describes mountains as “rock-ribbed and ancient as the sun”. In one chapter the young romantic rails against the boring names his fellow Pākehā have given to mountains. What glory would there be in dying, Pascoe asks, trying to climb a peak called Mt Percy Smith? A rather stuffy reviewer for the Guardian complained that Pascoe’s book had too many metaphors, and paid “too little attention to the technical problems of mountaineering”. I, for one, don’t regret Pascoe’s bias.

Pascoe’s most ambitious expedition took him all the way through the Southern Alps to Westland, where he found the people and their manners unfamiliar. Pascoe had never left Canterbury before; reading him, we are reminded of how narrowly many New Zealanders ranged in the 1930s, how alien another part of their own country could seem to them.

The Canterbury Mountaineering Club was disappointingly misogynistic: no women were allowed. At lower altitudes, though, a much more inclusive culture flourished in New Zealand’s many tramping and hiking clubs. Women and men tramped together, and in the green worlds like the Waitakeres and they often abandoned the conservative mores of New Zealand society.

Nude tramping became popular in the 30s, as young New Zealanders emulated the Freikörperkultur, or free body culture, of Weimar Germany. Bill Sutch is nowadays remembered as a grey-faced economist and a possible KGB spy; in the early 30s, though, he and his partner Morva Williams helped spread the gospel of nudity through the Victoria University Tramping Club.

A co-founder of the Working Women’s Union and the Family Planning Council, Elsie Locke already had a reputation as a feminist and left-wing activist in the mid-30s, when she discovered the delights of naked tramping in the Waitakeres. In a weighty and rather dull history of New Zealand tramping, Chris MacLean and Shaun Barnett solemnly record that Locke returned from one walk “sunburnt in unusual places”.

Locke increasingly began to see tramping as a way to explore remote and neglected parts of New Zealand. In her memoir Student at the Gates, she describes a 1937 journey down Waikato’s west coast, from Waiuku to Port Waikato all the way to Aotea Harbour. The area south of Port Waikato is colloquially known as Limestone Country; it is a place of caves and blind valleys and disappearing streams. Dubious land deals let Pākehā farmers in at the end of the 19th century, and Māori were increasingly isolated on scraps of the most marginal land.

Hiking across roadless hills — and keeping her clothes on most of the time — Locke and a friend found themselves welcomed into shacks where elderly women made them bread over open fires and spoke in a Māori-English hybrid. Only 50 kilometres from Auckland, the trampers had entered another nation. Although Māori suffered as much as Pākehā from the Great Depression, until 1936 they were eligible for only a fraction of the unemployment benefit their Pākehā compatriots received. The whare Locke visited were far from health clinics and schools.

Locke, had “never before been on a marae or inside a Māori house”. She came to realise that, in spite of the material poverty she saw, “untapped riches” existed in Māori culture. After returning to Auckland, she began a lifelong study of Māori history and language.

Robin Hyde. Photo: Alexander Turnbull Library.

Although the travel writers of the 1930s often discussed Māori, all of them were white. A Māori genre of English-language travel writing did not emerge until the 1950s, in the magazine Te Ao Hou. Published by the Ministry of Māori Affairs, Te Ao Hou was intended to be a “marae of words”, where communities increasingly split by urbanisation and cultural change could share news and tell stories.

Te Ao Hou published scores of accounts of journeys to Māori communities. Pākehā writers like Hyde and Pascoe reported their discoveries in an excited tone; the authors in Te Ao Hou were calmer. Their articles were as much concerned with old folklore and stories as with novel experiences.

In a 1962 piece called “Te Taou and the Sandhills”, Colleen M Sheffield describes the South Kaipara Peninsula. Cook had nicknamed this region “the Desert Coast”, on account of its vast dunes; Sheffield shows how Te Taou had learned to thrive in the desert over centuries. But Sheffield’s article is also a report on radical change: by the 50s the government was planting millions of pines on dunes, terraforming the landscape. Te Taou supported the transformation, and one of their number, a bush engineer of genius named Kelvin Povey, invented a machine that could sow marram grass in the sand between pine saplings.

In a 1968 article for Te Ao Hou called “The Titi Islands”, TV Saunders followed his Kāi Tahu relations on a muttonbirding expedition in Fouveaux Strait. Saunders packs three months’ food and brings salt to cure the birds he catches. He loads kerosene, so that he can light and heat his hut. Saunders celebrates the exclusive rights that Kāi Tahu maintain to the exploitation of the Titi Islands. For him, they are a “perfect dream-haven”, magically removed from New Zealand’s Pākehā-dominated main islands.

For many years, much of the domestic travel writing I have been describing could be accessed only in the backrooms of research libraries. Unclimbed New Zealand and Locke’s Student at the Gates are still out of print, but over the last decade both The New Zealand Railways Magazine and Te Ao Hou have been placed online, in searchable formats, as part of the New Zealand Electronic Text Collection.

We can no longer catch a passenger train through Northland or scale a previously unclimbed mountain. But as New Zealanders are again exploring their own country in record numbers, there is much in these texts that remains relevant, perhaps even urgent. New Zealand is still a nation in which an urban majority lives in ignorance of remote rural hinterlands. Many Pakeha have still to discover what Elsie Locke called the “untapped riches” of Māori culture. And the mountains that John Pascoe crossed remain both obstacles and inspirations.

Scott Hamilton has a PhD from the University of Auckland and has published books about the Pacific slave trade, the Great South Road, and British socialism. He tweets @SikotiHamiltonR

This story appeared in the January 2021 issue of North & South.